Fishermen’s Health and Safety in the Northern Tunisian Region (Southeast Mediterranean Sea): Risk Assessment

Oceanography & Fisheries Open Access Journal Juniper publishers

Abstract

Occupational health and safety is becoming more and more crucial to maintain a safe working environment for all types of vessels in Tunisia as maritime workers are exposed to work hazards on a daily basis. With the aim to respond to this national need, we sought, through this work, to diagnose this problem from two perspectives. On the one hand, we inspected the state of the Tunisian regulations related to the fishing activity. On the other hand, we tried to identify maritime hazards to which the crew might be exposed. To do this, we examined the working conditions of the high seas fishing vessels in the northern region of Tunisia particularly the physical environments (sound, light, heat, humidity) through inspections on board fishing vessels (trawlers).

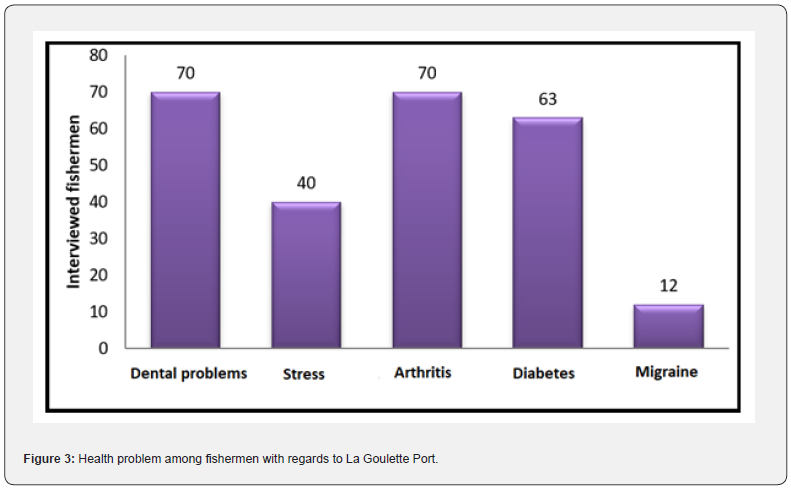

In order to identify the organisms that are involved in the maritime field, we looked at the legislative aspects by examining the archives of the administrations and the regulatory documents. In addition, surveys were conducted with 100 fishermen operating in the port of La Goulette. We noted that despite the increasing fishermen’s complaints about work and loss of profit in the fishing industry, the legislation on this subject is still meager. The diagnosis revealed that most fishermen have problems related to noise and lighting and they suffer from the impact of humidity, climatic conditions and bad weather. We also found that some health problems result from the fishing vessel being both a work platform and an unsustainable living environment. The majority of fishermen have problems with teeth (70%), stress (40%), rheumatism (70%), diabetes (63%) and migraine (12%).

Among the most common fishing vessel accidents are shipwreck (3.1%) and collision (24.7%) whose origin is mainly economic pressure and fatigue. Besides, the maintenance and operation of the vessel all have a direct impact on the safety and health of the seafarer. Eventually, the seafarers’ health and safety must address all aspects of the social, psychological, and physical well-being of fishermen. A national strategy and a preventive plan must be implemented to combat these scourges of accidents and occupational health hazards at sea. In addition, vocational training must be part of the workers’ rights for a more effective protection.

Keywords: Fishermen; Maritime hazards; Fishing vessels; Health and safety; Risk Assessment; Tunisia

Abbreviations: CNSS: National Health Insurance Fund; IMO: International Maritime Organization; EEZ: Exclusive Economic Zones; UTAP: Tunisian Union of Agriculture and Fisheries; SAR: Search and Rescue; VMS: Vessel Monitoring Systems

Introduction

The fishing industry is of paramount importance for the livelihood of millions of people worldwide as a primary source of income and food safety [1]. It provides around 40.4 million jobs in the fisheries sector, which accounts for a substantial number of the world’s population [2]. Globally, the sea fishing sector is acknowledged to be the most hazardous sector for employees, with significantly higher rates of fatal and/or severe accidents compared to other industries such as agriculture or construction [3,4]. In fishing operations, fish species interfere with the time allocated to harvesting, fishing methods, crew cohesion and risk-taking. On the other hand, protecting the health and ensuring safety of seafarers remain a federative priority [5-7].

While, it is crucial that the workplace provides a healthy and safe environment, unfortunately, this is not always the case. Maritime workers around the world face risks that threaten their safety and health every day. Not to mention fatal injuries, other less serious occupational accidents according to international data suffered by fishermen include, but are not limited to, bruises, cuts, puncture wounds, sprains and strains, fractures and even amputations. Many fish harvesters also experience health problems like back pain resulting from poor load handling or sliding injuries, sound-induced hearing impairment, and various infections [3,8,9]. No doubt, professionals are keen on the safety of their crews when it comes to weather conditions to which they may be exposed. Many of them keep up with innovative fishing technologies, equipment, and practices, and work on the constant improvement of the safety of their vessels [2,10]. Statistics show that deadly injuries in the fishing sector are declining in developed countries [11-13], while numbers are still high in developing countries [1,14].

Risk prevention for workers is a discipline that covers all types of activity in every sector. This includes avoiding risks; evaluating risks that cannot be avoided; combating risks at source; fitting the job to the worker (design of posts, choice of equipment, work methods, etc.); taking into account the evolution of technology; replacing what is dangerous by what is non-hazardous or less dangerous; planning prevention; giving priority to collective protection; giving appropriate instructions to fishermen; protecting fishermen from hazards that threaten their safety and physical integrity; promoting and maintaining the highest possible degree of physical, mental and social well-being of workers in all occupations; placing and maintaining workers in a work environment securing their physical and mental health [3,15]. Similarly, seafarers’ health and safety measures address the social, mental, and physical well-being of fishermen.

This topic remains of paramount importance and this study has been carried out to further dig into it with focus on the Tunisian context. It has been supervised by the Higher Institute of Fishing and Aquaculture of Bizerte and has been conducted in collaboration with the following national structures: the General Directorate of Social Security, the General Directorate of Medical Inspection and Occupational Safety, and the Regional Commission for Agricultural Development of Tunis (Fishing and Aquaculture District of La Goulette).

This work aims to examine the Tunisian regulations related to the fishing activity; to inspect the working conditions and the states of fishing vessels; and to assess the fishermen’ health and safety on board. Maritime fishing, an adventurous activity in the face of the common fisheries policy in the country: what protection is provided to fishermen while at work?

Material and Methods

Review of jurisdictional records and regulatory documents

In order to know the structures of social work, particularly those related to the maritime field, we looked at the social protection system and social funds, such as affiliation, contribution, pension system, and damage and benefits in case of work accidents and professional diseases. We also considered the legislative aspects, namely the conventions related to occupational health and safety ratified by Tunisian rights and codes. Upon the examination of the archives of the administrative bodies working on safety, health and labor law, we particularly focused on the Ministry of Social Affairs, which represents the focal point of all these institutions as well as the General Directorate of Medical Inspection and Occupational Safety, which is in charge of hazards, accidents, diseases and medicine at work. The National Health Insurance Fund (Caisse Nationale d’Assurance Maladie/ CNAM) provided us with statistics on the occupational accidents and diseases in the fishing sector.

This work was carried out at the level of the fishing port and the district of fishing and aquaculture of La Goulette. A survey on the fishermen’ occupational health and safety, physical environment, risks, accidents and diseases were conducted. The ships inspected had different physical environments, hazards, levels of safety and life-saving equipment.

Survey

A total of 100 fishermen out of the 729 fishermen operating in the port of La Goulette answered the questionnaire in the period of March 2020 and April 2021. We questioned 3 ship-owners, 18 captains, 14 boatswains, 10 mechanics, 19 mechanics’ helpers, 30 fishermen and 6 cooks. At the beginning of the questionnaire, we collected the following information: age, sex, level of education, type of fishing, fishing area, current position, date or year of recruitment, number of fishing trips and number of crew members they work with. The questionnaire also sought to find out who should be notified when something abnormal happens on board a ship, the working and organizational conditions, the preventive measures put in place by their ship-owner or captain and their motivation to work at sea. The seafarers were then asked about their feelings about safety while doing their jobs; whether they have encountered any occupational health problems at sea. We also wanted to learn how knowledgeable they are about their social security rights. With regard to occupational conditions on board a ship, we asked questions about noise (noise level), wearing personal protective equipment, and thermal/humidity conditions and the presence of ventilation systems. Other questions were about health conditions resulting from the ship’s movements, such as seasickness and means of prevention as well as electrical hazards (risk of contact with electric current, locking of electrical cabinets, periodic checking of electrical installations), lighting (complaints of visual fatigue, adequacy of lighting at workstations, etc.), and general hygiene rules (personal hygiene rules, sanitary compliance with International Maritime Organization (IMO) rules). The last questions investigated occupational accidents and diseases (leave for health reasons, having had an accident at work or an occupational disease, the nature of injuries and following complications) as well as risks and accidents associated with different positions of the vessel: dockside, underway, or fishing.

Inspection of a fishing vessel

The bridge, the main deck, the engine room and the freezing room were chosen as the main places of the seafarers’ activities. This part of the study examined the physical environment on board a fishing vessel (trawler). Noise mapping of the various workstations was realized to diagnose the situation in terms of noise exposure and to identify the workstations deemed to be a priority within the aforementioned locations on board. The approach was based on the measurement of noise exposure levels observed at the time of ship operation and the aim was to propose recommendations in relation to the nature of the source and the type of exposure.

Noise measurements were carried out using a SMART SENSOR AR824 digital sound level meter. The lighting environment measurements were conducted with a calibrated luxmeter, brand testo 545 where the average illuminance (Em) is the average of the illuminances measured at a number of significant points. The luxmeter cell is placed horizontally in relation to the height of the work surface. The study of the thermal environment and humidity was realized by means of a questionnaire as well as measurements with an anemometer and a thermal environment thermo-hygrometer B & K type Testoterm.

Statistical analyses

The results were tested to determine if they were normally distributed using a Kolmogorov-smirnov test. Statistical analyses of data was conducted using STATISTICA (8.0) software package for Windows. A one-way ANOVA, followed by a post-hoc test, was used. A probability of 0.05 or lower was considered significant.

Results

Occupational diseases and work accidents in the fishing sector

Statistics with regards to occupational accidents indirectly promote positive attitudes towards prevention and efforts to fend off the recurrence of accidents. These objectives can only be achieved if all the stages of the statistics elaboration (survey - analysis - classification - calculation of indicators and exploitation) are carried out. In fact, we can classify the consequences of accidents into three categories: individual, social, or economic.

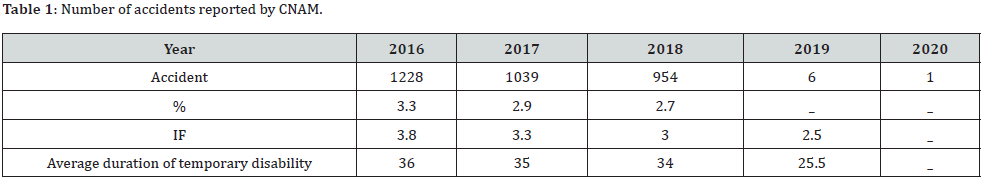

According to the collected numbers (Table 1), work accidents in the years 2016, 2017 and 2018 decreased significantly from 3.3% to 2.7%. In 2019, there were 6 reported work accidents and only one in 2020. The frequency index, (Number of reported work accidents with lost time *1000/ Number of employees), dropped from 3.8% to 2.5% between 2016 and 2019. The average duration of temporary disability was lower in 2019 with 25.5 compared to 36 in 2016.

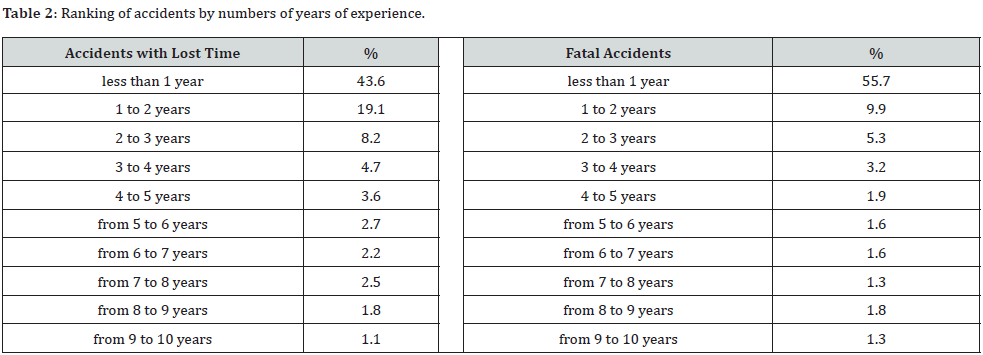

Fishermen with less than one year working experience are the most affected by accidents, whether with lost time (43.6%) or death (55.7%). On the other hand, for those with 1 to 10 years’ seniority, the rate varies between 19.1% and 1.1% for lost-time accidents and from 9.9% to 1.3% for fatal accidents (Table 2).

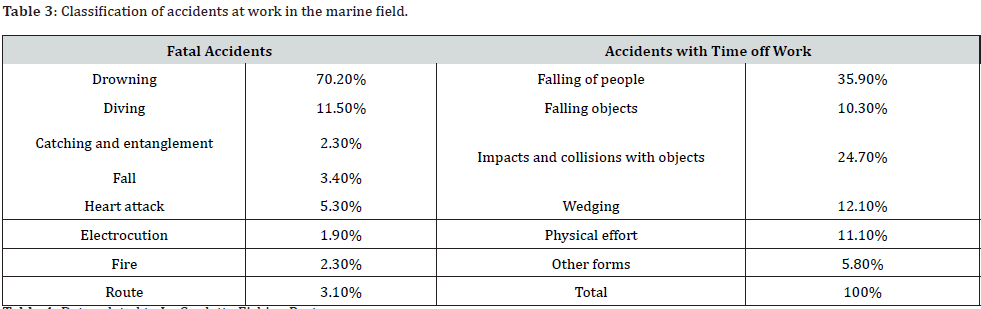

For occupational accidents with time off work, falling is the most frequent (35.9%), followed by shocks and impacts by objects which represent 24.7%. The other forms of accidents range between 12.1% and 5.8%. For fatal accidents, drowning is the highest (70.2%) followed by diving (11.5%). The other forms have an impact between 5.3% and 1.9%. In total, 43% of accidents at work in the fishing industry involve seamen with less than one year experience. This percentage rises to 55% with regards to fatal accidents. A total of 70% of accidents are caused by falls, collisions and entrapments (Table 3).

Working conditions at La Goulette fishing port

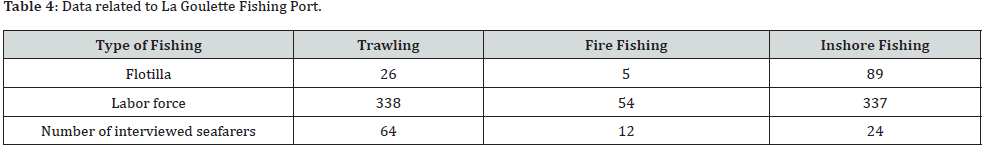

The fishermen interviewed at La Goulette Fishing Port were male, aged between 17 and 64 years, of whom 14.67% had a valid physical fitness certificate. All these fishermen have no employment contracts or written work commitments. They are all on board with a professional seafarers’ booklet following a verbal agreement with the ship-owner with no time limit. The average age of the fishermen who filled out the questionnaire is 42 years, where the majority is experienced and adult fishermen (30-59 years-old). The data collected with this interview are summarized in table 4 below.

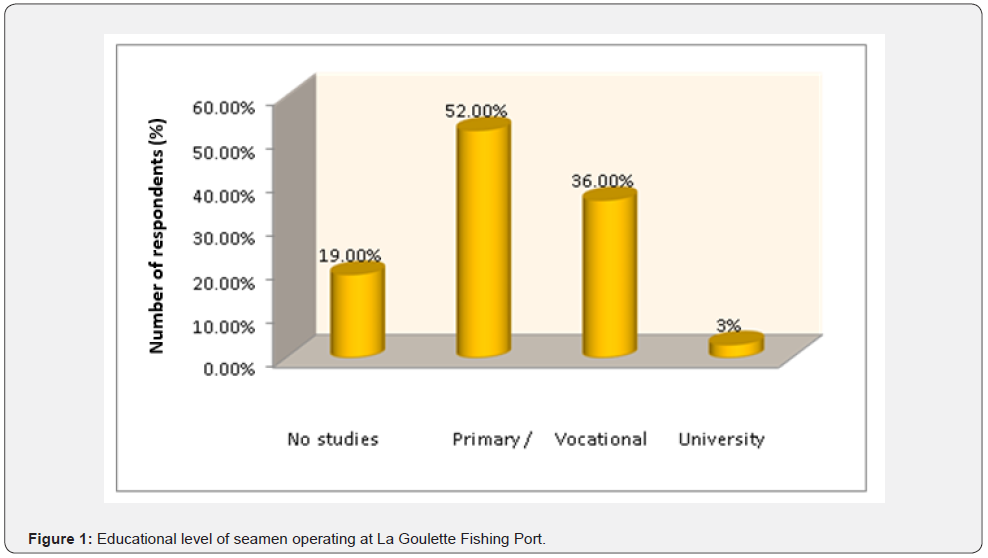

The survey helped identify the following statistics: 64% of the fishermen work on board trawlers, 12% of the fishermen practice fire fishing and 24% are embarked on coastal fishing boats (Table 4). Fishermen with no formal education represent 19%, while those with primary or secondary education represent 52% of the population. Those with vocational training represent 36%, while 3% have a university degree (Figure 1). Fishermen wish have a primary level of education are more oriented towards this profession (ANOVA, p<0.05).

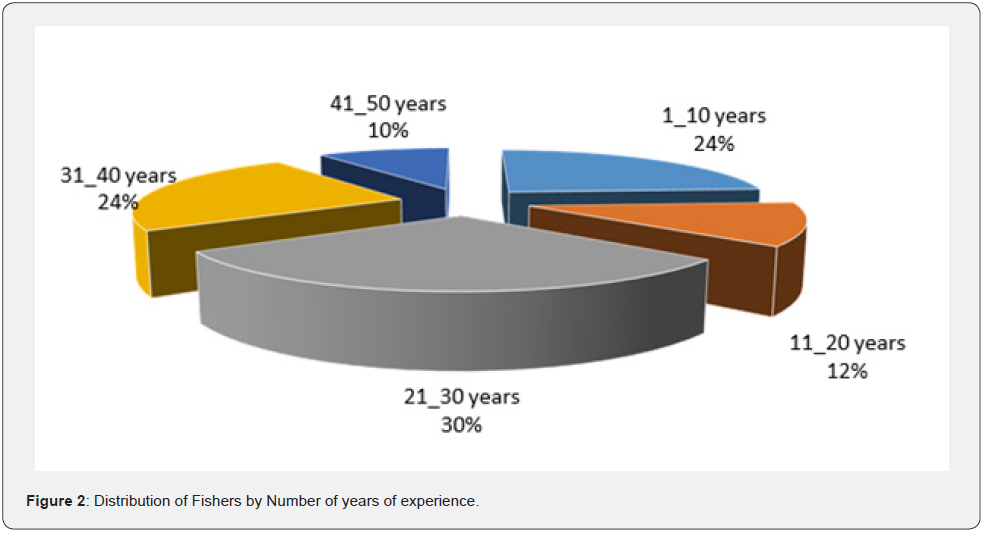

In total, 30% of the fishermen interviewed have worked between 21 and 30 years, while 24% have worked between 1 and 10 years. The same percentage (24%) is observed among those who have worked between 31 and 40 years, whilst 12% of the fishermen have 11 to 20 years professional experience (Figure 2).

We have identified a lack of training and awareness-raising on health and safety for ship-owners and fishermen. When an incident occurs during work, 21% of the seafarers deal with it personally. On the other hand, 14% of the fishermen settle it according to a well-defined and pre-planned procedure and the majority (75%) call upon a third party (a superior, a colleague, or a specialized service). In total, 80% of the interviewees consider the working conditions and its organization to be bad, 15% of the fishermen see them as good and only 5% find them excellent. A large percentage of the fishermen (70%) think that there are no safety or prevention measures implemented by the vessel owner/ manager, 25% feel the measures are insufficient and only 5% believe that the measures are sufficient. Also, only 12% of the fishermen feel safe while carrying out their activities. Half of the fishermen reported they had encountered work-related health problems. Their distribution is summarized in figure 3.

Among the 100 interviewed fishermen, 70 of them reported dental problems. The same number suffers from rheumatism, while 63 ones suffer from diabetes, 40 are over-stressed, and 12 have migraine. 68% stated other issues, such as not enjoying their work and tasks. 16%, though, stated they are motivated to work. All the fishermen questioned said they had no problems either with the crew members or with their supervisors. Two thirds of the fishermen stated they had not been able to balance work and private life. 72% had no idea about their social security rights, whilst 17% had some knowledge about them, and only 11% knew them perfectly well.

Working conditions

Regarding working conditions, the state of the deep-sea fleet at La Goulette Fishing Port is critical with the continuous operation of units that are already worn out. The noise environment is considered unacceptable by 30% of the fishermen, especially in the engine room, which forces 24% of the fishermen (mechanics and assistant mechanics) to shout to be able to be heard. In addition, not all the fishermen wear personal protective equipment such as earmuffs and earplugs.

58% of the fishermen perceived the thermal environment as unacceptable in winter and summer. On the other hand, 13% rated these conditions an unacceptable in winter, but acceptable in summer; 16% of the interviewees noted that they are unacceptable in summer and acceptable in winter. While 7% of the fishermen thought they were acceptable in both winter and summer time. Regarding ventilation facilities, one-quarter of the fishermen reported that there are none. Humidity was considered unacceptable in winter by all interviewees.

Among the 100 interviewed fishermen, 33% complained of visual fatigue at night. The lighting of the workstations, galley, gangways and ladders was considered sufficient by most fishermen. 11% of fishermen believed the floodlights on the fishing deck hinderer their work. However, in total, 65% of the fishermen thought that the level of lighting was sufficient to carry out the required work, especially at night. A total of 46% of fishermen said that there is a risk of contact with electric current. While, 30% stated that electrical cabinets with naked live parts are kept closed. Furthermore, 60% of the fishermen stated that the electrical installations are periodically checked by the mechanics or by private companies. Out of 100 fishermen, only 12% complained about sea sickness, especially at the beginning of the tides. All the fishermen underlined that there are no available prevention means against seasickness. The instability of the vessels makes the work difficult for 70% of the fishermen. Only 17% of the interviewed fishermen declared that they applied personal hygiene rules. Nearly 67% of them wash their hands after handling the products and before each meal. Besides, not all sanitary facilities comply with IMO rules.

Occupational accidents and diseases

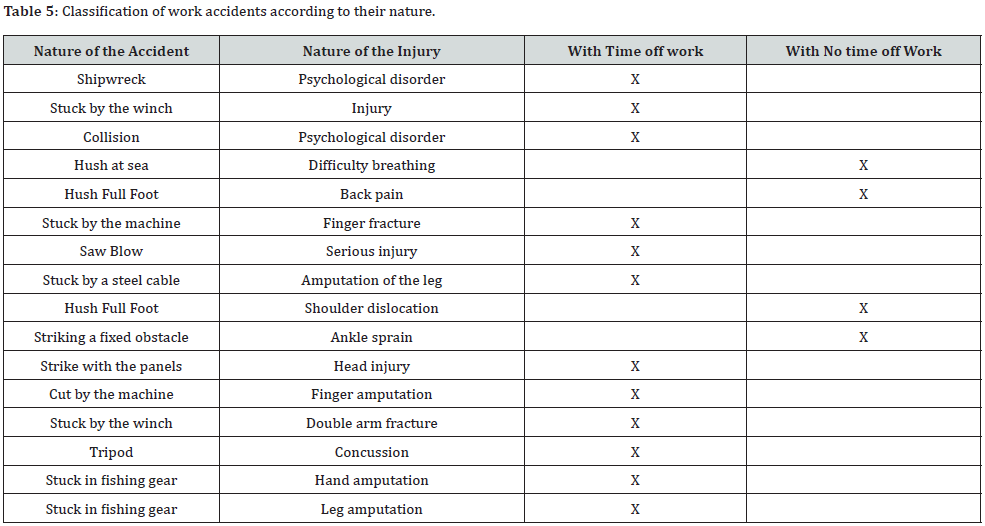

No one among the 100 interviewees had time off for health reasons during the year 2020 with the exception of one fisherman who had 4 days off due to an occupational disease. Table 5, below, summarizes the accidents the fishermen operating at La Goulette Fishing Port had encountered. The time off work does not depend on the seriousness of the accident or the nature of the injury, but on the decision of the ship-owner.

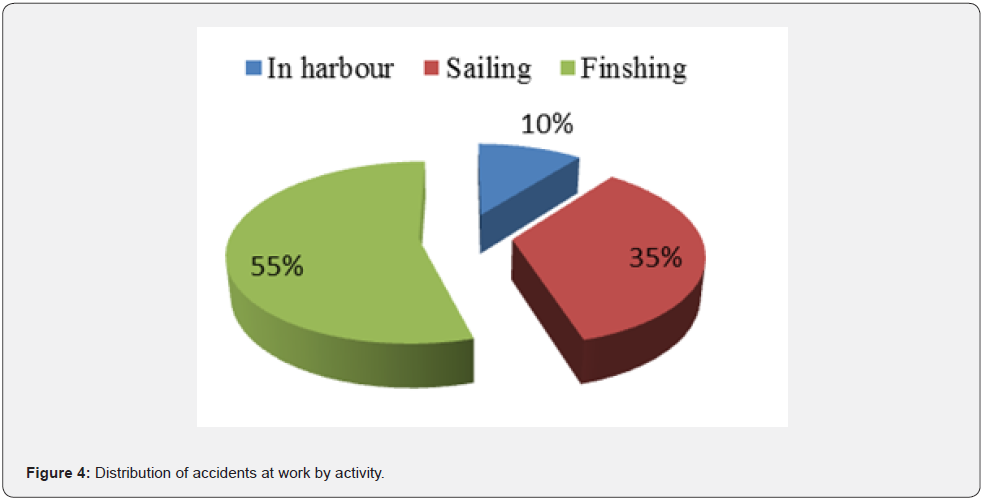

The number of occupational accidents at sea is significantly higher than the one at dockside. This pattern figure 4 is dependent on the time spent by the vessel at sea or at dockside as a result of its activity. The results of the Student’s T Test (at p<0.05) for the different types of accidents that could occur on board a vessel, during fishing operations or at dockside showed that there is a significant difference between these two locations (p=0.0008). Similarly, there is a significant difference between the number of accidents at dockside and underway (p=0.003).

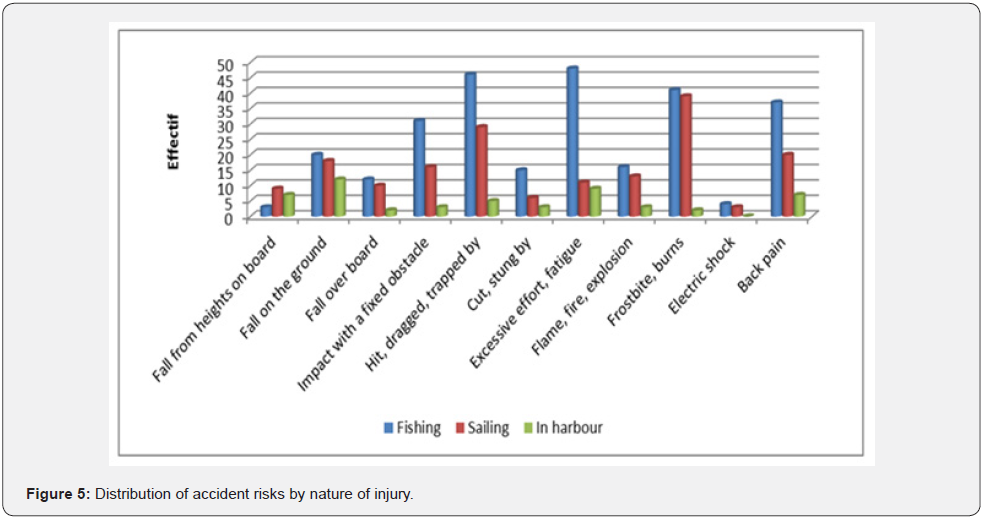

The distribution of perceived risks according to the type of accident and the location of the vessel is summarized in figure 5: We noted that the main risks of accidents are noted during fishing activities. In addition, fatigue, overexertion, back pain, injuries and entrapment are the main accident risks regardless of the vessel’s state of mobility (Figure 5).

We have noticed weakness at the level of legislation and great social injustice towards the fishermen, which leads to a decrease in profitability and productivity.

Sound environment

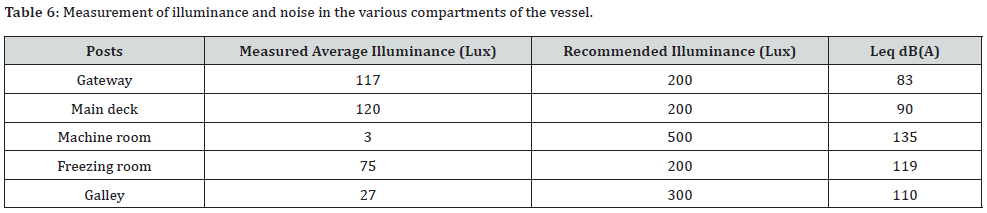

On board a ship, the main sources of noise are the main engine, the gearbox and the propeller. On the other hand, the auxiliaries, ventilation system, exhaust and hydraulic system generate negligible noise. To calculate noise level, we used Leq, which is the equivalent sound level, and it represents the total noise exposure, or alternatively, an average noise energy level during the period of interest. The results of the survey show that almost all the workers in the four compartments of the vessel (bridge, main deck, engine room and freezer room) are exposed to noise levels above 80 dB, which represents a health hazard. In the engine room, the noise level is very high, at about 135 dB. Exposure to excessive noise levels for long periods of time has repercussions not only on the hearing system itself, but also on the body in general.

Illuminance

Light on board must ensure the safety of the vessel and help prevent wrong maneuvers and accidents. In addition to facilitating work, a good lighting system helps to maintain and enhance the general well-being of everyone on board. The results of the measurements carried out on board fishing vessels (Table 6) show that the level of illuminance in the various workstations is significantly low compared to the recommended level. It is particularly low in the engine room, galley and freezer room.

The effects of poor lighting on the operator are very diverse and are not always specific: Ocular effects (heavy and painful eyeballs, burning, tingling, redness); Visual effects (blurred vision, presence of a veil, dark spot, difficulty in perceiving details); General effects (headaches, general fatigue, etc.); Moreover, lighting conditions that are poorly adapted to the task, force operators to adapt restrictive postures, which in turn constitutes a risk for the spine).

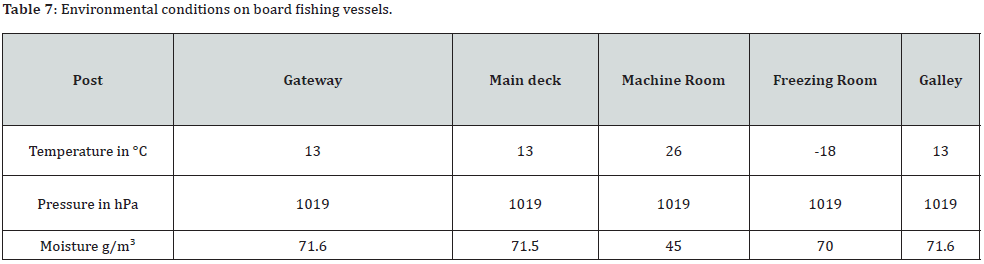

Thermal environment and humidity

Thermal environment plays an important role in the health, safety and comfort of workers. This is an issue whether in hot or cold conditions. Physical discomfort is very common in the workplace. It is quite easy and spontaneous to express the sensations experienced when faced with the thermal environment to which one is subjected: sensation of heat or suffocation and cold, associated with characteristic effects such as sweating, shivering, etc

According to table 7, the temperature (in °C) varies from -18 in the freezing chamber to 26 in the engine room. The pressure is stable at 1019 hPa at the various stations. The humidity ranges from 71.6 g/m³ in the bridge and the galley and 45 g/m³ in the engine room.

Evaluation of working conditions

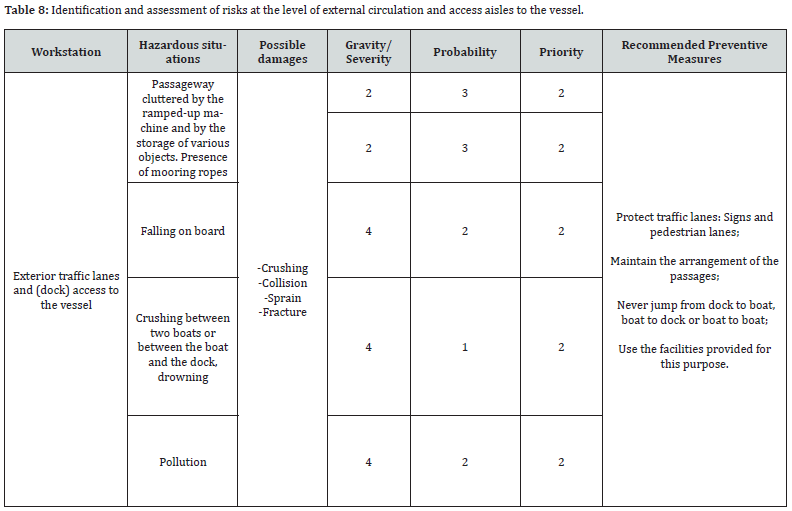

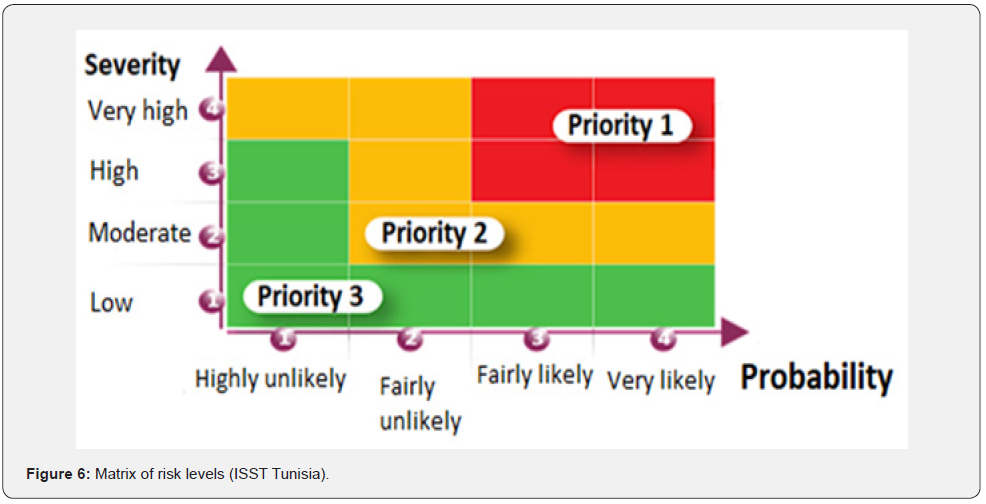

We proceeded to the evaluation of the risks deduced from the identified sources (hazards) according to the following risk level matrix: for each identified risk situation we estimate the probability of occurrence (Pr) and the severity of the potential damage (Gr) and then we determined the level of priority of action based on the following scheme (Figure 6):

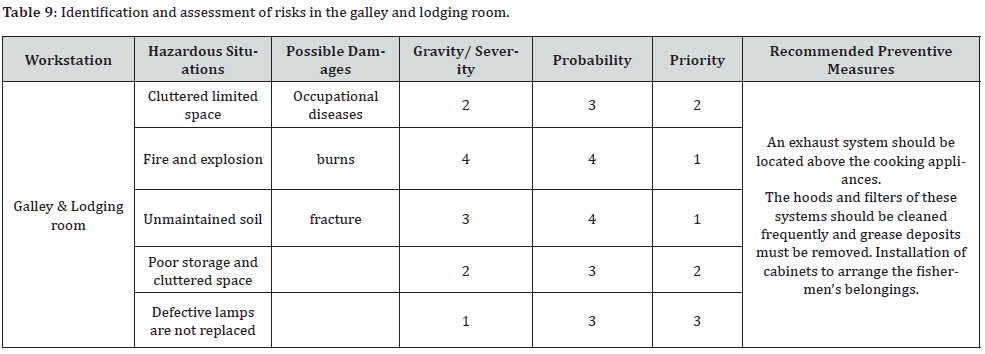

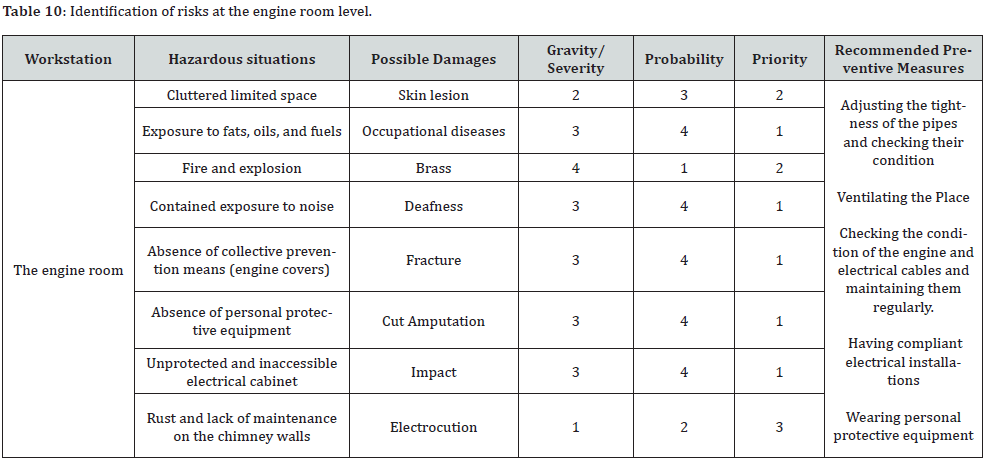

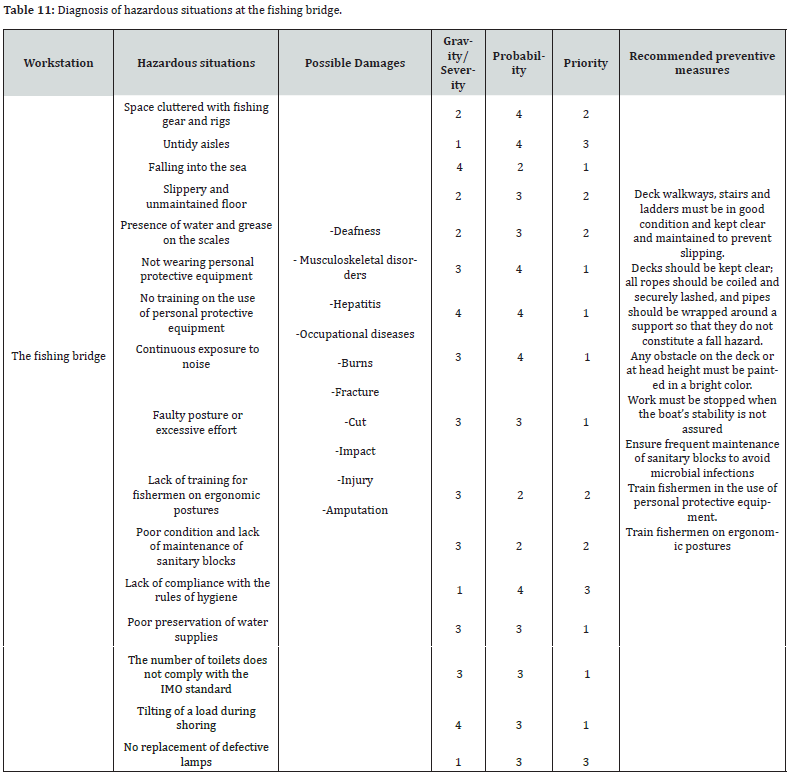

All the hazards related to the different compartments of the vessel are summarized in the following tables 8-11:

Close examination of the life-saving equipment on board the trawlers showed that the life rafts are, in the majority of cases (62%), inaccessible and that they do not meet the standards of the SOLAS Convention. Life jackets are also inaccessible and are not enough for all the crew members. Generally, only one dry chemical fire extinguisher is placed on the bridge.

Discussion

Fishing hazards

Fishing is notorious for being one of the most hazardous occupations. In spite of the significant role it has in food production and the substantial contribution it makes to the world economy, it is confronted with occupational hazards and health risks of all sorts [1]. Many studies point out that both fatal and non-fatal injuries are overly high among fishermen compared to other occupations [4,16]. The main reason why fishing is so dangerous is that humans are terrestrial species. For humans, being immersed in water is a lethal hazard [17]. Cold, wind, rough seas and high physical workloads are but a few of the risks that fishermen are exposed to [18]. On board a ship, tasks are performed in tiring conditions and on moving, exposed and slippery platforms where seafarers have to work in awkward positions. These circumstances create constant physical strain and contribute to ongoing fatigue, compounded by the excessively long working hours. In fact, fatigue in itself increases work hazards; as it undoubtedly interferes with seafarer’s ability to perform their job efficiently and safely [8,19-22]. Fishermen are forced to perform multiple tasks for which they are not necessarily adequately trained. Some types of fishing gear are dangerous by their very nature, especially in bad weather [23]. In addition, seafarers’ health and well-being have a tremendous impact on their maritime safety; a tired seafarer is a source of accidents [24,25].

Safety at sea is essential for fisheries management

In recent years, fishermen have witnessed a desertification of the sea and an overexploitation of fishery resources as a result of anarchic and illegal fishing. The latter have caused the disappearance of juvenile fish resources as well as the aquatic plant cover [2,26,27].

With open access to fisheries, fleet capacity exceeds the yield of exploitable stocks. In many countries, this issue was solved with the adoption of the 1982 United Nations Convention. This convention divided the “High Seas” into the exclusive economic zones of coastal states, allowing each nation to control fisheries up to 200 nautical miles from its coast [28]. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (1994) further set out the rights and obligations of coastal states with regards to the management of their exclusive economic zones (EEZ) out to 200 nautical miles. The Maritime Labor Code refers to these periods as contracts of employment. The place of the accident is decisive, but without any categorical limit. Indeed, accidents on land may fall within the scope of the legislation on occupational accidents at sea. For this reason, the seafarer’s registration on the crew list is equivalent to having an employment contract allowing him to be in connection with the ship. This registration includes the time before and after embarkation. Case law is strict as to these situations and an incident cannot be considered as maritime work accident only when the seafarer was very close to the ship and at a time when his presence is justified by service considerations. Thus, a seafarer on call who encounters an accident or is the victim of an illness is only covered if he is performing a service on board [26]. The Fishing Vessel Code also states that the company is under an obligation to provide seafarers with adequate knowledge, training and guidance to allow them to operate in conditions of safety, to have arrangements for consultation with seafarers on matters of health and safety, and to maintain procedures for the reporting and investigation of on-board mishaps and accidents [29].

Social protection scheme for fishermen

It is common knowledge that commercial seafarers operate in extreme weather conditions, frequently far from medical emergency facilities and rescue services [30]. Like other workers, fishermen are entitled to humane work practices. The International Organization Maritime Labour Convention, 2006, as amended states (Article IV) that “Every seafarer has the right to: a safe and secure workplace that complies with safety standards; fair terms of employment; decent working and living conditions on board ship; health protection, medical care, welfare measures and other forms of social protection” [31]. Employers’ affiliation to social security schemes is compulsory for all workers. It must be done within one month of the hiring of employees. Every shipowner is required to join the social security fund [32,33].

Registration with the National Social Security Fund (Caisse Nationale de Securité Sociale CNSS) of fishermen on foot, fishermen who own their own boats and work alone, fishermen employed on boats of less than five tons and small ship-owners is carried out through fisheries administration [32].

Insurance

Safety of a fishing vessel is a multifaceted interplay of different components which involves people including proprietors, captains and crew members. Another major player is machinery like gear and vessels. Besides, it goes without saying that the working environment is a crucial element including weather and systems of management. In fact, high waves because of extreme weather conditions have often flooded fishing vessels and led to disasters [34]. In order not to run the risk of losing all or part of the value of his ship, a ship-owner has an interest in insuring his ship. The master must have a copy of the insurance policy on board and be familiar with all the terms. He is required to take great care of the vessel and its equipment. In case of damage or accident, he must write a sea report and notify the insurer, limit the severity of the loss and save everything that can be saved. The insurance of a fishing vessel includes all risks or total loss and abandonment [35].

Hazards in relation to the fishing sector never ceased and will never cease. However, it is crucial to continue taking and implementing safety measures as these help combat this phenomenon and reduce risks mainly due to advances in technology worldwide [17]. The hostile and changing environment in which the vessels operate is the most important source of danger. The movements of the vessel, as well as the movements of the different parts of the rigging, are also major hazards [36].

The design, construction, maintenance and operation of the vessel all have a direct impact on safety and health. Hazards vary depending on the type of fishery, fishing grounds and weather conditions, vessel size, equipment, and the work of individual fishers. Bad weather and engine failure are the main risk factors for all vessels [17,36,37]. The seafarer must work on board a ship, but accidents can happen even on land. Through the identification of accidents’ causes, preventive procedures and actions can be taken in order of priority [17]. These accidents are divided into seven categories:

a) Sinking is equated with the total loss of the vessel. In case this occurs, it is most likely that the crew face the same fate. Structural failure of the ship and water ingress into the hull is serious problems that can lead to loss of buoyancy. Even large modern ships can be broken up in severe storms. In December 2020, on the way back from the coast of Zarzis to Sfax, the boat “Wissem” sank off Mahres with 11 sailors on board [38].

b) Grounding is the accidental or deliberate detention of a vessel at a shallow depth. In December 2019, a Togolese flagged vessel ran aground on the coast of Bizerte due to bad weather [39,40].

c) Collision occurs when two vessels crash into each other at the entrance or exit of a port, or in open sea. These accidents are very frequent in reduced visibility. Vessel crashing may result in major property damage and life loss. An example of collision which took place between a Tunisian ship and a Cypriot container ship on October 12, 2018 [34,41,42].

d) Fire is considered to be one of the main serious and dangerous accidents which can threaten the safety of a ship. The most common natural causes are lightning, sparks, chemical reactions, short circuits, or gas leakage. However, most fires which occur on board are caused by humans [43,44].

e) An ingress of water is the unintended entry of water into a vessel as a result of an opening in the hull below the waterline. It is considered a serious accident for ships. Following one of these accidents, the shipowner must write a detailed sea report, indicating all the events and damages. We can mention the case of the tug “Alixander” which took on water in June 2008 [45,46].

The recurrent causes of accidents are mainly related to human factors, which include fatigue, stress, poor maintenance, inattention or carelessness, routine, drug or alcohol abuse, navigational errors, personal relationships and working conditions [21,47].

In addition, technical factors are important causes of accidents and can be summarized as the absence or non- compliance with similar standards at the design, construction or conversion stage of the vessel; poor condition of machinery; absence or malfunction of equipment, in particular alarm systems and fire-fighting systems; use of unsafe fishing gear; insufficient personal safety or survival equipment; disregard of stability measures; and lack of systematic monitoring [16,34,47]. External factors include mainly weather conditions. In fact, fishermen are under economic and competitive pressure to take more risks due to downsizing and increased working hours. Actually, accidents caused by fatigue and exhaustion are omnipresent [21,47].

Studies and statistics from national health and welfare services in many countries show that non-fatal injuries are very common in the fishing industry. Despite the high figures quoted, it is clear that such injuries are grossly under-recorded. In general, statistics on injuries and fatalities in the fisheries sector are inadequate and incomparable between countries, due to different data collection and classification systems [1,17]. The situation of the seafarer is special; he lives in a limited space with no way out. This space is his workplace and his daily living space. This is why the old Labor Code (Article 742-1) refers to a special regulation. Seafarers are not covered by the provisions of the social security code for occupational accidents and diseases that occur outside the framework of the maritime employment contract. The Tunisian labor code covers all types of trade, which are covered by several codes except for the maritime trade. The maritime labor code is weak in terms of health and safety and needs to be reinforced. Moreover, we noted that there is a lack of documentation on fishermen’s health and safety in Tunisia. National policies regarding safety in the fishing industry must be presented along with an unwavering commitment to a regulatory regime, as well as the necessary resources. Enforcement must be considered at every stage of the formulation of regulations, not as the final consequence [48].

Land-based law is progressing slowly, but maritime law is still far behind. This difference results from archaic provisions in the maritime labor code such as working hours or the total absence of provisions on certain issues. It is essential that fisheries regulations are reviewed and amended to address problems and take account of their origins; the process of reviewing regulations must be as dynamic as the sector to which they apply. The establishment of the national working groups on safety at sea could be a step in the right direction [49]. Fishing boats have been designed with working surfaces on which fishermen are exposed to cold, heat or humidity. The design of an air-conditioning system adapted to the frequented areas must be well thought of in terms of thermal comfort, noise level, and air cleanliness. The efficiency of the system will depend directly on the individual adjustment possibilities in each cabin [17,50-52]. Normal lighting in all cabs shall be of the order of 200 lux. Where there is more than one occupant in a cabin, reduced lighting shall be obtained so that movement does not unduly disturb the resting men. The localized bunk lighting system must achieve a level of 200 lux. The results of this study revealed that fishermen have a different understanding of safety than the government and that there is a need for a better understanding of the fishing culture and the way safety is approached. These findings highlight the need to involve fishermen in the process of regulating safety and the human factor related to safety at sea.

For optimal functioning and effective safety on board, the coherence between the crew, the boat and its equipment is essential. In fact, this has proven to be really rare in Tunisia. In many of the accidents described, the lack of adequacy between the crew, the boat and its equipment is the main factor causing losses [48,53]. The heterogeneity of the crews, due to their different training and professional experience, creates important communication problems, which is a determining factor of the observed accidents [47].

Standardization of data collection across countries or regions is an ambitious goal. This idea is important especially for comparative studies. It is necessary to collect accident data in each region to facilitate planning and prioritizing preventive measures. Eventually, developing countries are in great need of appropriate injury, death and health reporting systems in the fisheries sector [1]. Only by knowing where and how accidents occur can we find the appropriate means of action. The types of fisheries are very diverse. Vessels range from trawlers to coastal barges. The causes of accidents obviously depend on the type of fisheries involved, the vessel, the weather, the sea state and the port facilities [47,53]. Fishing vessels are not included in the great part of the international maritime conventions and, to date, there is no applicable global regulation on the safety of fishing vessels, or the training of their crews [17]. The fisherman is generally at the origin of most accidents: insufficient training, lack of experience and skills, carelessness, and fatigue due to lack of personnel.

Safety at sea is a particularly sensitive issue in developing countries for several reasons. The comparatively smaller size of the maritime workforce, besides the relative invisibility of this labor group lead to a situation where their social rights remain less discussed than other vulnerable groups [31]. Appropriate reporting systems do not exist for injuries at sea, and injuries often go unreported [1]. Implementing practical measures to prevent accidents and health problems is critical to better health and safety in the fishing sector [1,3]. The development of a prevention program to identify risks, evaluate them and set up an action plan is a common approach for all personnel operating in the fishing sector. In this sector, in Tunisia, the control of working conditions on board vessels is very limited. Collaboration between the Labor Inspectorate and the fishing sector is of vital importance: to avoid a feeling of impunity due to the lack of control of the activity; and to ensure that real communication between the administration and the seafarers contributes effectively to preventing and reducing the risks of accidents at work.

According to the records of the Tunisian Federation of Insurance Companies, many fishermen who have had an accident during their working life are unable to work for some time or usually end up being disabled. These hazards pose financial and social difficulties for these fishermen and their families. Insurance services have been shown to reduce the vulnerability of fishermen and their families to shocks caused by work-related accidents and to contribute to the creation of sustainable livelihoods in the fisheries sector. In other sectors, insurance has also facilitated the development of a culture of safety and risk awareness and sought to improve safety standards and working conditions [33].

The fishing sector is classified worldwide among hard jobs. However till present, a high number of fishermen are still not affiliated. Moreover, the surveys carried out by the CNAM are very meager and ineffective. No employer/ship-owner has ever been sanctioned because of neglect of fishermen’s social claims. In addition to the negligence of the CNAM, the fishermen’ unawareness of their social rights, the lack of awareness of shipowners of fishermen’s maritime social rights and their greed play a very important role in this anarchy. Therefore, reliable and strict laws must be put in place for the organization and improvement of this activity.

In addition, we noted the absence of the involvement of UTAP as a union defending the fishermen’s interests, safety and health at sea. The results of the noise measurements in the various workstations obtained in the framework of this study show that almost all the workers are exposed to noise levels above 80dB, which represents the danger zone. The results of illuminance measurements show that the illumination level at the various workstations is relatively low compared to the recommended level. This is the case for all the different ship compartments except the main deck. We also used the risk level matrix for the evaluation and identification of work conditions. This method consists of estimating the risks in terms of severity, priority and probability in order to implement relevant preventive actions. By comparing the working conditions’ evaluation results of this study with research results in other fields, we have found that the marine working environment presents multiple varied occupational risks. Accidents are often fatal or they lead to serious disabilities.

Conclusion and Recommendation

Safety and health at work is nowadays essential for all types of vessels. In the face of increasing complaints from fishermen about work-related losses in the fishing industry, there is little legislation in this area. In addition, there is poor enforcement of legislative rules by most vessels.

In order to achieve maximum safety at sea and to ensure real security for people and property, the necessary material means should be provided and the political will should be directed towards the adequate application of health and safety requirements [2]. The human factor, an essential element in the prevention of accidents at sea, is also an important factor in the occurrence of such accidents. The human factor alone will not be able to improve the current state of health and safety at sea if it lacks the necessary material resources. A competent crew with sufficient members and in good physical and moral condition, on board a substandard vessel, face risk at sea. Thus, occupational safety, health, and wellness require careful management and dedication on behalf of owners, employers, and all crew members. Such an approach can significantly reduce the risk of death, injury and ill-health to people in the workplace [3].

The physical fitness certificate is considered by fishermen as a procedure to get the booklet, but most of them suffer from health problems related to noise and lighting. All fishermen complain from the impact of humidity, weather conditions and bad weather (sea state in general). Some health problems result from the fact that the fishing vessel is both a work platform and a living environment whose support (the sea) is unstable, and whose climatic environment is often unfavorable.

The majority of fishermen have dental problems (70%), stress (40%), arthritis (70%), diabetes (63%) and migraine (12%). The ship’s movements make it very difficult to perform tasks on board. Indeed, when the sea is rough, the seafarer has to make an extra effort, on the one hand to ensure his balance and on the other hand to maintain his posture to perform his task. Thus, a simple and easy job when done in good weather becomes difficult, painful and sometimes risky in bad weather. Bad weather degrades the conditions for rest and relaxation and disrupts sleep. These kinds of workplace contexts naturally put employees at an elevated risk for mental health issues. The consequences of the work rhythm are well observed among fishermen. As the days go by, fatigue sets in, with rest periods being too short and disrupted by excessive noise levels or difficult weather conditions. It is clear that this fatigue is a cause of some on-board accidents.

The most common causes of fishing vessel accidents are sinking and collision. The main causes of these accidents are economic pressure and fatigue. The maintenance and operation of the vessel all have a direct impact on the safety and health of the seafarer. The risks vary according to the type of fishing, the fishing grounds and the weather conditions. On deep-sea fishing vessels, the fishing gear and other heavy equipment put the crew at great risk of death or injury. On small vessels, the risks are mainly capsizing while hauling in a large catch, being swamped in heavy seas, or being struck by a larger vessel.

Non-fatal injuries typically include broken arms or legs, head and neck injuries, and amputations of fingers, hands, arms and legs. In addition, many injuries go unreported because they do not result in prolonged job loss or financial compensation. These injuries are impossible to quantify or classify, but they are very common and involve physical damage such as cuts, wounds and sprains. These health risks appear to be accepted by fishermen, while they would be considered intolerable in most land-based occupations. A national preventive plan strategy must be put in place to combat these scourges of accidents and the health and safety problems of seafarers. Effective approaches to safety at sea around the world and at all levels are based on the following three lines of defense:

a) Prevention is the safest and most cost-effective element: with appropriate equipment, training, experience, and information dissemination it is possible to avoid getting into trouble in the first place.

b) Survival and self-rescue: equipment, training and attitudes necessary to survive and perform self-rescue operations when things go wrong.

c) Search and Rescue (SAR) is the most expensive and least effective of the three levels: alerting, search and rescue systems, which are used if the first two lines of defense fail. The SAR system is linked to the national VMS satellite surveillance system.

In addition, vocational training must be part of workers’ rights for effective occupational health and safety protection. Continuous training programs must be improved, taking into account the constant evolution of maritime techniques, in order to allow professionals’ well-being during their career. These professional training courses should cover topics related to the safety of both workers and vessels.

To Know More About Oceanography & Fisheries Open Access Journal Please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/ofoaj/index.php

For more Open Access Journals in Juniper Publishers please click on:

https://juniperpublishers.com/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment