Are the Solar and Battery-Powered Lights used for Dagaa Rastrineobola argentea Fishing a Threat to the Nile Perch Lates niloticus Fishery in Lake Victoria?

Oceanography & Fisheries Open Access Journal Juniper Publishers

Abstract

For decades, the harvesting of Dagaa (Rastrineoboala argentea) from Lake Victoria and other waters bodies relied on lanterns as the primary source of light attraction. Being one of Lake Victoria’s top four economically significant fisheries, Dagaa has a significant impact on the macro- and microeconomics of East African nations. Recent innovation for harvesting Dagaa using solar and battery-power lights, have raised conserns about the sustainability of Nile perch. The current declining Nile perch is associated with the introduction of solar and battery-powered lights. To validate the consern, TAFIRI conducted a Dagaa fishing light research. Dagaa fishing research was conducted in offshore waters around Bwiru in Nyamagana district and questionnaires administered in Ilemela district in May 2022. It was revealed that solar light caught 6 fish species and battery-powered had 5 with relatively higher catch rate dominated by Dagaa solar (60.2 kg/boat/day) and battery-powered lights (105 kg/boat/day). The widest range of species were caught in boats using no fishing light (12 species), with catch rates dominated by Haplochromines (15.1 kg/boat/day). Nile perch catch rates were relatively low in (i.e., battery-powered 18.8; solar 15.7; and no light 1.8) kg/boat/day. Finally, it was determined that catching immature fish, such as Nile perch, is more frequently associated with fishing in inshore areas and fishing illegally, rather than accusing any types of fishing light. While it was found that competition for the same fishing ground was the main source of the conflict between Nile perch and Dagaa fishermen, fish theft by Dagaa fishers and Nile perch patrol boats swindling the solar and battery-powered lamps was another instance of conflict. Strengthening law enforcement may help to eliminate all of these discrepancies, including those that result from the use of illegal fishing gear and techniques and those that restrict use of drifting gill nets in Lake Victoria.

Keywords: Solar; Battery-powered; Dagaa; Conflict; Fishing; Nile perch

Introduction

The use of fabric materials as fishing nets was used at the beginning of the Dagaa (Rastrineobola argentea) fishery in Lake Victoria, followed by the introduction of lantern lamps (Karabai) [1-3]. The fishery is currently one of Lake Victoria’s four commercial fisheries, the others being those for haplochromines, Nile perch (Lates niloticus), and Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) [4,5]. Fishing in the Dagaa fishery entails scooping up the aggregated captures, which occasionally contain by-catch such as haplochromines and Caridina [6]. Other fish species taken in the fishing activities include young Nile perch attracting dispute between Nile perch fishers and the Dagaa fishers in Lake Victoria. Dagaa is a native fish species to the lake while Nile perch is an allien fish species, first introduced in the Ugandan water of Lake Victoria from Lake Albert during the 1950’s and early 1960’s [7-10]. Due to a drop in catches, tilapiines, which are also common by-catch in the Dagaa fishery were as well introduced including Tilapia melanopleura, T. zilii, Oreochromis leucostictus and O. niloticus [11]

Both Dagaa and the Haplochromines have enormous potential for small-scale trading in local and regional marketplaces, acting as an affordable source of protein for both human and animal sustenance [3]. In addition, a sizable amount is transported to poultry factories to prepare animal feed [12]. The yearly harvests of Dagaa have shown a rise from 509,598 tons (55.4%) harvested in 2014 to 566,570 tons (64.6%) landed in 2015. This is due to the introduction of solar and battery-powered lamps for Dagaa fishing to the lake [13].

In contrast to when kerosine pressure lamps were in use, the usage of solar and batter-powered lamps has given rise to concerns and accusations that it has increased the bycatch of juvenile Nile perch during Dagaa fishing. Fishermen have come a long way in developing new techniques and technologies, and they frequently catch young Nile perch as a result. Other fishing tactic is by fishing Dagaa without light, also called locally as “kimyakimya, manyamunyamu, kumbakumba” in Tanzania, is one of these novel inverted fishing techniques, as are the conventional methods where solar and battery-powered light are not employed throughout the entire fishing activity.

Sustainable fisheries resources in Lake Victoria depend on the monitoring of fishing technology and the provision of scientific guidance for fisheries management [14]. To evaluate the impact of solar and battery-powered lamps, and the magnitude of bycatches, particularly the Nile perch in the Tanzanian portion of Lake Victoria, a study was commissioned by the Ministry of Livestock and Fisheries to the Tanzania Fisheries Research Institute (TAFIRI). The main goal of the study was to determine the quantity of fish by-catch that is caught when solar and batterypowered fishing lamps are used in Lake Victoria, Tanzania.

Materials and Methods

Study site

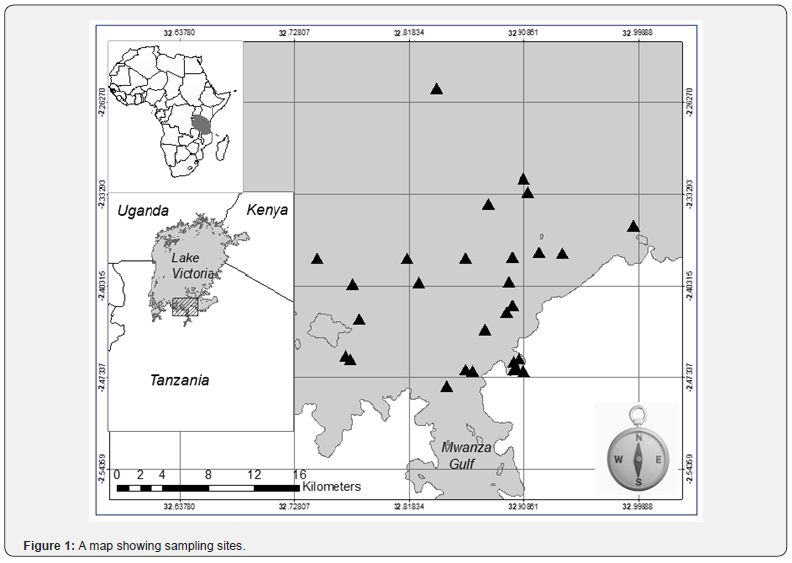

Actual Dagaa fishing for experimentation was conducted in the Mwanza region at randomly selected locations in the offshore waters of Bwiru, as shown in figure 1. All fish sample landings were sorted and measured at Bwiru landing site. To get information on the social aspects of fishing community, we administered questionnaires at Mswahili landing site in Nyamagana district, and at Bwiru, Kayenze-Ndogo, and Kayenze-kubwa landing sites in Ilemela district. All the districts involved in this study were of Mwanza Region (Figure 1). These locations were chosen because they are easily accessible, nearly all Dagaa fishers utilize either solar or battery-powered lamps (new light fishing technique), and they landed a significant amount of Dagaa landings.

Data collection

The six fishing boats used in this investigation all had small seine fish nets, mesh size 8mm, and vertical nets joined between 12 and 16 panels. Boats were divided into categories according to the type of fishing lights. We had two boats with custom-made battery-powered lights, two boats with manufactured solar lamps, and the last two boats with no light sources (i.e., kimyakimya/ manyamunyamu). Under the direction of a scientist on each boat, the boats were operated by fishermen with comparable fishing expertise. This was done so intentional to have the similarity of these features to guarantee the sampling unit’s consistency.

Sampling was conducted according to the standard operating procedures (SOPs) for collecting biological information from the fishes of Lake Victoria [15]. During sampling, large-sized fish, such as catfish and Nile perch, were separated as soon as the catch was caught, and their weights and numbers were noted. A 5.0 kg unsorted sample was taken from the rest of the catch (lump), which was primarily made up of Dagaa and Haplochromines. The sample was counted, weighed, and classified by species. To produce a weight per species in the lump, such weights, determined from the sample, were multiplied by a rising factor (lump weight to sample weight). These weights were added to the corresponding species weights measured from the lump if they were from species assessed before taking the 5.0 kg sample; otherwise, weights measured from the lump constituted total species weights.

Finally, the species composition of the by-catch and its contribution to the Dagaa fisheries were determined by weight, using species other than the Dagaa. To ascertain the effect of solar and battery-powered lights on the size structure of Nile perch or any other fish species caught, length frequency data were gathered. The whole length of the Nile perch was measured (to the lowest cm). Primary techniques were used to gather socioeconomic data by conducting in-person interviews at the beach with various stakeholders while distributing a semi-structured questionnaire to them. A round table discussion with fishers who were also members of Beach Management Units (BMUs) was conducted to find the existing root cause of conflict between the Nile perch and Dagaa fishers.

Data analysis

Data on catch and length frequency were entered into a Microsoft Access 2016 database that was made expressly to handle, store, and query the data. For the purpose of evaluating the catching effectiveness of the various fish species, a query exporting species-specific capture rates for each fishing boat was made. Social-results were displayed as frequencies, ratios, and percentages that were produced in the IBM SPSS statistics version 21.

Results and Discussion

Fishing grounds explored using different light sources

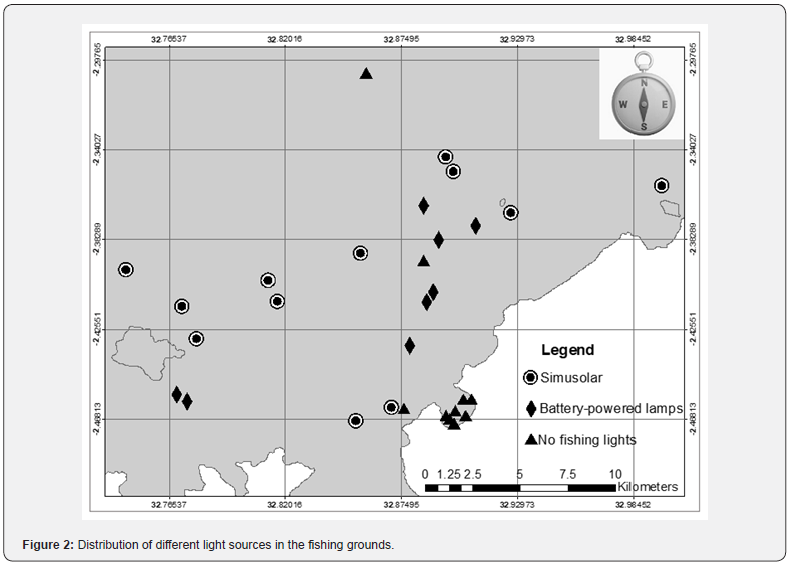

Three categories of light sources were studied including simusolar lamps, battery-powered lamps and no fishing lights. Since the research team did not have any way to influence the choice of fishing ground, the distribution of the sampled points shown in figure 2 depicts the usual distribution of the different sources of light in the fishing grounds.

It was, therefore, noted that fishing without light is mostly done nearest to the shore and particularly in sheltered waters close to landing site of origin. Such areas are mostly nursery and breeding grounds for most fish species. The other two categories appear to be fishing in relatively more open waters.

Catch composition

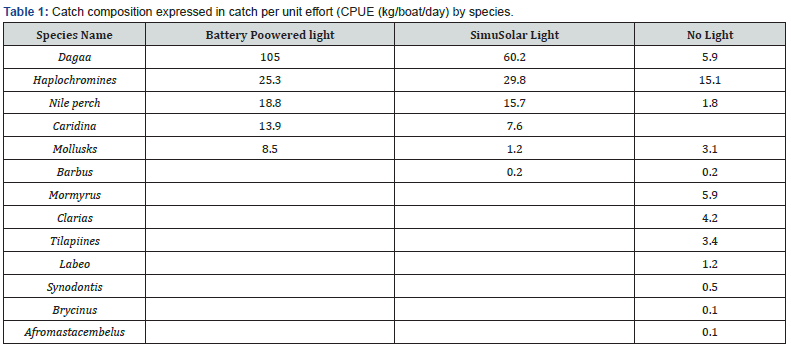

Thirteen species were caught in this study whereby boats using battery-powered lamps had the smallest number of species (5) but relatively higher catch rates dominated by Dagaa by far (105 kg/boat/day). Simusolar lamps had the next highest catch rates, also dominated by Dagaa (60.2 kg/boat/day) among the 6 species caught. The widest range of species caught (12 species) was recorded in boats using no fishing light but had the lowest catch rates dominated by Haplochromines (15.1 kg/boat/day) (Table 1). This pattern is consistent with the observation made earlier in this study that fishing without light is more concentrated in the sheltered nearshore waters where most species breed and feed.

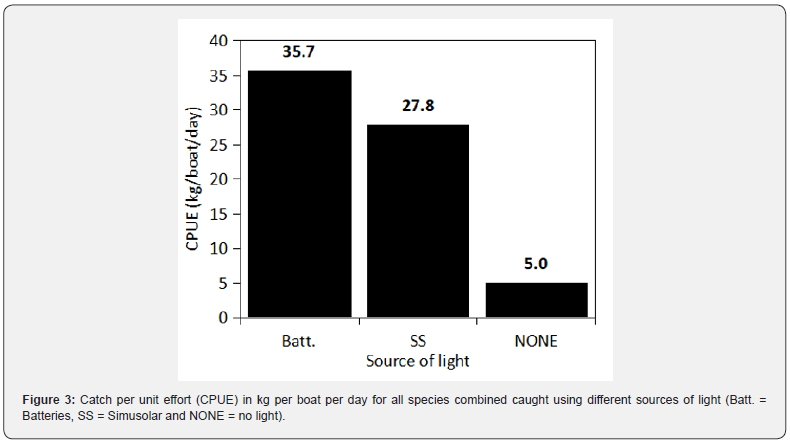

Comparing the overall catch rates of the three categories studied, irrespective of species caught, battery-powered were had the highest catch rates followed by Simusolar and No light fishing (Figure 3).

Size structure of Nile perch bycatch

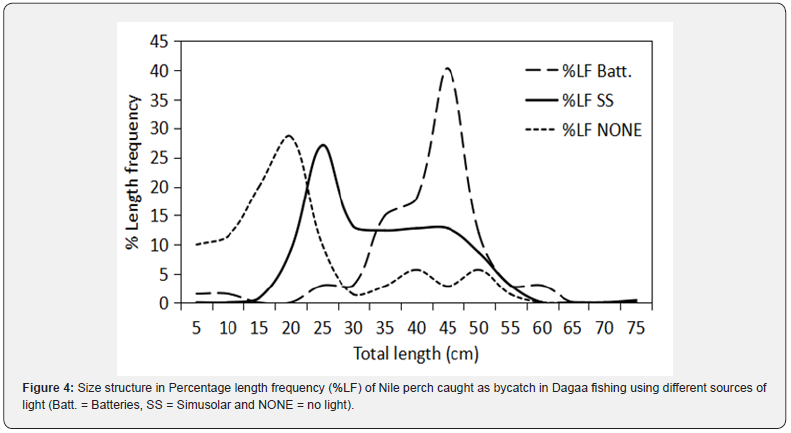

The use of no light in the inshore water while fishing for Dagaa catches Nile perch at the smallest sizes (17 cm TL). Simusolar and battery-powered lamps attracted relatively large size of Nile perch with battery-powered lamps catching Nile perch at a relatively the largest size (45 cm TL), yet immature when considering Nile perch slot size limit, a size at first maturity (Figure 4). These results suggest that battery-powered lamps are relatively safer for Nile perch by-catch in this context, than any of the other light sources.

Socioeconomic aspects

Sampling locations visited during the study were Bwiru and Butuja landing sites in Ilemela district, and at Mswahili landing sites in Nyamagana district. A total of 53 respondents were interviewed, of which 96.2% were males, the majority aged between 31 and 50 years. The interview included 66% fishers, 30.2% boat owners, and other stakeholders involved just in a small number. Most respondents (54.7%) were involved in fishing for the past ten years, with the majority (71.7%) participating in the Dagaa fishery, most (98.8%) using solar and batterypowered lights, and very few using kerosene pressure lamps. Most respondents admitted to having noted the decline of Dagaa recently and the reasons they gave were due to climate change (39.5), illegal fishing (28.4%), increased fishing effort (fishers, boats, and nets) (27.2%), and a few pointed to be caused by the use of solar and battery-powered lights (1.2%) currently operated in the fishery.

Solar lamps encountered in use in the Dagaa fishery were supplied mainly by Simu solar company (52.6), Sagar (26.3%) whereas the normal batteries, mostly small sized used as source of light by motorcyclists, were obtained from retail shops (13.2%), and solar lamps of Warsha company was the least supplier (7.9%) of solar fishing lights. The majority respondents (94.4%) revealed that expired batteries used in fishing for Dagaa, are said to have good deal. They are normally sold as scrap, and then exported out of the country as raw materials to manufacture new products. Others disclosed about the products being kept at homes (2.8%) for use as sources of light at their homes, and an equal proportion number of the respondents (2.8%), reported to be thrown in the lake as waste products.

Fish by-catches

The Dagaa catch, sometimes is associated with other fish species as by-catches. About 29% of the respondents admitted that Nile perch were caught as by catch with other fishes such as Haplochromines (30.2%), Caridina (18.6%), Synodontis (9.3%), and other fishes including Nile tilapia (12.8%) (Figure 5). About 77 percent of those polled agreed that the status of Nile tilapia, a popular fish species in the lake zone, has declined. The decline was also noted in Nile perch whereby a higher percentage of the respondents (55.4%) attributed the decrease of the species to the rampant use of illegal fishing gear; some percentage (25.2%) to climate change; and lower percentage (15.1%) to increased fishing effort.

A large proportion of respondents (81.0%) disclosed that in the past five years the leading illegal fishing gear was monofilament, others (14.3%) indicated to be beach seine nets and a few (4.8%) pointed cast nets, and some accused Dagaa net-like fishing gear operated near shores (in fish breeding and nursery grounds) known by the local name of “kimyakimya, karashara/luwaluwa” to be among the illegal fishing gear.

Effect of solar and battery-powered fishing lights

It was finally revealed from the focus group discussion that solar lights have no effect because they are good, portable, stay a long time, and still give light even if they are immersed in water. Solar and batter-powered lamps continue to give light, which has no harm to fishers even in case of damage. But kerosene pressure lamps have records of many incidences of accidents [16]. The lamp can explode, leading to deaths; when it rains, it may faint; and the kerosene (e.g., fuel) may contaminate Dagaa, thus reducing its quality. In reality, solar and battery-powered lights have identical features in performance, the only difference is in the charging system. Solar lamps are charged by the panels exposed to the sun, whereas battery-powered lights are charged by Alternative Current (AC) normally from electrical power.

Conflicts among resource users

We discussed potential conflicts between Nile perch and Dagaa fishers at a round table with fishermen who were also Beach Management Unit (BMU) members. The initial conflict was caused by natural mass fish kills, particularly of Nile perch, which is referred to as “Kiferezi” in Tanzania. Every year, the phenomenon happens during the rainy season, primarily in April and December. A boat could land between 2 and 10 kilograms of Nile perch captured in a Dagaa seine during “kiferezi,” and most boats can catch up to 30kg in total, plus additional fish as by-catch, in a period of four fishing days. While not always guaranteed, Dagaa fishermen may sometimes catch 1-5 kilogram of Nile perch per boat per day during regular fishing conditions.

Competition for the fishing grounds is the cause of conflict on other instances. When the Nile perch fishery first began, they were the sole fishermen active primarily in offshore areas. They left their gill nets set and unmoving to fish all night. Later, fishing practices were changed to get more fish in order to meet the rising demand in domestic, regional, and global markets. In order to enhance their chances of acquiring the biggest harvest, fishermen let their gill nets drift while hunting fish. Fishing with drifting gill nets in Lake Victoria, is however, prohibited by sections 52 (I) of the Fisheries Regulations, 2003 and 66 (1) (j) of the Fisheries Regulations (Amendment) of 2009 [17,18]. It means that almost all the Nile perch fishers using gill nets in Lake Victoria are now fishing illegally.

The new invention of solar and battery-powered lamps for fishing Dagaa, is more effective and user-friendly even in inclement weather than kerosene pressure lamps [19]. Kerosene pressure lamps are normally operated by fishers who have relatively small seine net of few panels operated in small paddled boats.

Fishing light innovation went hand in hand with the development of large paneled fishing nets operated in relatively big boats powered by outboard engines. The advancements allowed Dagaa fishers to enter the offshore fishing grounds that were previously only accessible to Nile perch fishermen. The Nile perch fishermen’s gill nets were now restricted losing the ability to move. The drifting nets then get entangled with other Dagaa nets as they are fishing or stacks on the floating lamps. In some occasions, the Dagaa fishers were tempted to retrieve the nets and remove the fish, leaving the nets to continue their journey without fish. Because of this, Nile perch fishermen were unable to catch enough fish for the day accusing those who are using solar and battery-powered lights in the Dagaa fishery. In contrast, Dagaa fishermen accuse Nile perch fishers of removing some of the solar and battery-powered lights that they found to be impeding the movement of their fleets when they are on patrol for the security of their set gill nets [20].

Possible reasons for the decline in Nile perch

During the round table discussion, it was revealed that presence of illegal fishing gear such as beach seines, monofilament nets, under-sized gill nets, and others known by local names of Roborobo, Kimyakimya, Karashara, Luwaluwa, and Kumba Kumba which when thrown in water, do collect all types and sizes of fish, real threatens the sustainability of the Nile perch fishery. Other reasons for the declining Nile perch are increased fishing effort by the number of fishers, crafts, and gear, some of which are vertically joined to explore most of the water column. For example, Dagaa fishers joins several panels of seine nets for pelagic fish, but sometimes they fabricate big fishing nets of more than 16 panels to extend down to the bottom with an intention of catching Nile perch, which are also bottom-dwellers. Finally, we are confronted with environmental changes that cause rise and fall of water level, temperature, and increased pollution by waste materials, which may have also contributed to the declining of Nile perch in Lake Victoria.

Conclusion and Recommendations

Due to the non-selective character of the Dagaa nets used in Lake Victoria, the majority of Nile perch caught as bycatch in Dagaa fishing are relatively young fish. Rather than accusing any of kinds of fishing light, catching immature Dagaa is more commonly connected with fishing in inshore waters and use of non-selective fishing gear. There is therefore a need to enforce the closure period to stop Dagaa fishing for the entire month to release pressure on the fisheries. It is also important to outlaw the use of illegal fishing gear such as beach seines, monofilament nets, undersized multifilament gill nets, and others locally known as Roborobo, Kimyakimya, Karashara, Luwaluwa, and Kumba Kumba, through strengthened management measures. To prevent conflicts between the two fisheries actors (Dagaa and Nile perch fishers), we should strengthen law enforcement including those limiting on fishing by drifting gill net in Lake Victoria.

https://juniperpublishers.com/ofoaj/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment