The Importance of Pinnacles and Seamounts to Pelagic Fishes and Fisheries off the Southern Baja California Peninsula- Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers- Journal of Oceanography

Abstract

We evaluate the importance of seamounts to pelagic fishes and fisheries in the Gulf of California by creating an inventory local seamounts, analyzing the seasonal abundance of pelagic species an inter-annual time scale at a single seamount using underwater visual census, ultrasonic telemetry and fisheries observation, and assessing the fishermen and fisheries that depend on seamount ecosystems. We arrive at an inclusive definition of seamounts and consider a seamount to be any submarine peak or ridge abruptly rising from a level sea floor The abrupt topographic nature of these features lead to its ecological significance, as a site attracting a diversity of fishes in relatively high abundance. We describe and encourage science-based management of seamount fish assemblages and present four major areas we believe will need further study if we are to understand and better manage seamount ecosystems and their related fisheries, including causation of productivity surrounding seamounts, scales of oceanographic processes impacting seamounts, connectivity of species to seamounts and the socio-economic impact of ecosystem management on fishermen.

Keywords: Seamount; Pelagic fish; Ecology; Fisheries management; Gulf of california .

Introduction

Pelagic habitat is an important component to developing future fisheries management strategies [1,2]. Pelagic fishes, including tunas, jacks, dolphinfish, billfishes and sharks, are important marine resources worldwide. Wide ranging commercial fisheries as well as more localized artisanal and recreational fisheries target these economically and ecologically important species [3-5]. Populations of many of these species appear to be in decline due to intense and sustained fishing pressure [6,7]. Overfishing and inconsistent fisheries management have resulted in reduced fish populations Sosa- Nishizaki 1998 [4,7], destabilized marine ecosystems [8], and impoverished coastal communities throughout the world's oceans.

The management of pelagic ecosystems is particularly challenging to fisheries managers because the species that inhabit the pelagic environment are often highly migratory and the fisheries for them can be irregular, decentralized and across international borders [5,9]. Recent focus on the threats of pelagic overfishing [6,10] has raised the need to further our understanding of these ecosystems and the fisheries that target pelagic species. However, a lack of critical scientific information about the ecology, distribution, and abundance of these species, as well as information on fisheries themselves has hampered management and conservation efforts [4,10]. Reliable data on pelagic ecosystems are critical to promoting more sensible fisheries management decisions [6].

Shallow seamounts and similar topographic features in the ocean are known to be associated with rich stocks of pelagic fishes (Uda & Ishino 1958) [11-13]. This abundance may result from flow dynamics caused by the interaction of ocean currents with abrupt isolated topographies [14] that increase the concentration of phytoplankton and/or abundance of planktonic grazers [15-17]. Secondary and tertiary consumers may find this productive habitat optimal for feeding, reproduction [16], or use them as landmarks to guide their movements back and forth between daytime resting places and nighttime feeding grounds [1,18]. Marine management strategies that hope to protect pelagic species must identify and consider such pelagic "hotspots" [2].

The Gulf of California has many shallow (upper 200m), intermediate (200 to 400m depth) and deep (more than 400m deep) seamounts, especially in its western margin where some rise from very deep water (>1000m) to shallow depths (<30m). Except for a few recently studied seamounts in the southern Gulf of California, seamounts have been for the most part uncharted in this region. Little is known about their bathymetry and general physical characteristics. Traditionally, what is known about these seamounts (e.g. location, approximate depth and some physical features) comes from anecdotal sources, particularly from local fishers and sport divers. In recent decades, the El Bajo Espiritu Santo (EBES) seamount in the southern Gulf has been intensively studied, and it is home to a diversity of pelagic fishes [12,13,19]. These sites are the daytime habitat of five species of snapper (Lutjanidae), four billfish, the dolphinfish (Coryphaenidae), three jacks (Carangidae), four tunas (Scombridae), four sharks (Carcharhinidae, Sphyrnidae), and numerous other smaller species of fish [18]. We have carried out over the last decade a collaborative effort at this seamount. Studies were conducted to describe the interaction of currents with the seamount [20,21], the diversity and abundance of plankton, [17], seasonal residency of planktivorous and predatory fishes [18], and the trophic ecology of large pelagic fishes (Richert 2007).

More recently, we have begun examining fisheries within the southern Gulf of California. Small-scale fisheries play a significant social and economic role in regions bordering the Eastern Central Pacific Ocean. Subsistence fisheries along the Pacific coast of Mexico, including the Gulf of California, remain important resources to rural communities [4]. While the fisheries in the Gulf of Mexico (Atlantic Ocean) have been increasingly monitored, little information is available on Mexican small-scale fisheries located in the Pacific Ocean and Gulf of California. The potential impacts of small-scale commercial and sport fisheries on marine resources demand accurate evaluation to maximize management of these resources. The artisanal and sport fisheries located on the southern Baja peninsula (Baja California Sur, BCS) represent small-scale fisheries that may impact the region's marine resources [3,4]. Mobile artisanal fleets of pangas, small fiberglass boats, fish for various species during different seasons, and a sport fishing industry coexists in this region and flourishes because the abundance of large species is a recreational attraction. Failure to understand and manage fishermen will hinder effective management of marine resources [3,22], and increased study of fishermen is needed among fisheries research.

Past fisheries management has often focused on maintaining maximum biologically sustainable yield, rarely considering economic and social impacts. As we seek to manage fisheries and conserve the marine environment, it is imperative that the biological, economic, and social interactions within fisheries are understood. Management strategies should also take into account the interests of all fishing groups in the sight of increasing competition while continuing to incorporate biological information about the fish populations.

We evaluate here the importance of seamounts to pelagic fishes and fisheries in the Gulf of California. An inventory is created of local seamounts based on multiple sources. Secondly, the seasonal abundance of pelagic species was determined on an inter-annual time scale at a single seamount. Thirdly, the economic value of seamounts is assessed based on interviews of artesanal fishermen and the catches of recreational fishermen.

Materials and Methods

We focus our description in the coastal waters of the Gulf of California around the southern Baja Peninsula (BCS), Figure 1. The presence of diverse topographic features including islands, offshore banks and seamounts, as well as dynamic oceanographic conditions resulting from interacting oceanic currents at the mouth of the Gulf [23] make this region a natural laboratory for studying pelagic fishes and their associated fisheries. This is also an ideal study area because of the interaction between artisanal and sport fisheries [22], and the proximity of seamounts where we will assess fish populations.

Identification and description of topographic features

Seamounts in the Gulf of California are not well-documented. We consulted a variety of sources for information about seamounts in the Gulf including:

I. Bathymetric charts and maps of the Gulf of California (published and unpublished),

II. Oceanographic cruises performed by the authors,

III. Local fishermen from La Paz, San Jose, Cabo San Lucas, and Loreto.

We reviewed bathymetric maps of the region to identify seamounts in the Gulf of California. These maps were carefully examined for the presence of distinct seamounts. Only properly charted seamounts indicated by obvious depth contours and name were included in the inventory. However, there were several unnamed topographic features in which we described on the basis of depth contours and verified their presence among the different maps. The following charts and maps were examined: [24-31].

More detailed information on the topographical features of seamounts has been obtained during oceanographic cruises by the authors throughout the Gulf from the late 1970's until recent years.

Description of pelagic fish assemblages

We employed multiple techniques to determine how fish communities change with seasonal oceanographic conditions, including underwater visual census, ultrasonic tagging and fisheries observation. We recorded surface and subsurface water temperature with electronic loggers (Onset Computer Corporation, StowAway Tidbit) moored at a single seamount, EBES, and compared this record to the relative abundance of pelagic fishes recorded during underwater visual censuses (UVC) conducted at EBES from 1999 to 2004. Transects were conducted using SCUBA and began at the south end of the seamount ridge. Divers swam or drifted in a northwesterly direction and recorded species that were encountered in the pelagic habitat during a 40 minutes census. Visibility over the seamount was recorded and ranged from 7m to >20m. Jorgensen (2005) present a detailed description of the method of estimating the number of individuals observed of each species durng a SCUBA dive or drift. An index of abundance was calculated for this article based on these monthly censuses, which involved taking the scores for each species, averaging them per month, and then normalizing them so that they varied between 1 and zero by dividing each value by the highest value.

We employed the ultrasonic tagging techniques of Klimley et al. [18] to determine fish residence patterns at the EBES seamount. An ultrasonic tagging study produces a continuous record of the presence and absence of fish bearing individually coded beacons without the difficulties and biases inherent to census techniques and fisheries catch data. Two ultrasonic listening stations (Vemco Ltd., VR01) were moored at EBES in 1998, and redeployed in September 2002. In addition to a comprehensive study of the residence of 23 yellowfin tuna at EBES [18,19], five planktivorous Caranx caballus (green jack), five predatory Seriola lalandi (yellowtail), and two predatory Sphyrna lewini (hammerhead shark) were tagged at EBES with coded, ultrasonic tags with a life of two years (Vemco Ltd., V-16) in September-November 2002. Attendance records of the tagged fish were downloaded from the listening station every 3- 4 months and the batteries replaced at 12-month intervals. Records of tagged fish species were analyzed for short-term residence patterns.

We visited with managers of sportfishing fleets to obtain records of catch. We located and obtained a comprehensive database of sport fishing information at the East Cape Smokehouse in Los Barilles. This database recorded information on sport fishing charters and catches, as well as sea conditions and temperatures from 1999-2006. Data on number of charters and anglers was collected daily, compiled into weekly numbers, and related to water temperature. Total number of fish captured was also recorded. Using these two values, catch per unit effort (CPUE) was calculated as numbers of charters per week to provide a useful parameter for evaluating fisheries.

Survey of fishing camps and ports

We visited seasonal artisanal fish camps and sport fishing ports along the coastline of southern BCS from 2003-2006. Seasonal fish camps and sport fishing ports on both the Pacific coast of the peninsula and on the Gulf of California coast were mapped beginning in 2002 and 2003, while recording information on fishermen and boats. Local fishermen were interviewed to determine the number of boats per fishing camp and the percentage of effort directed at fishing at local seamounts. Initial interviews were conducted with a total of 75 fishermen, 48 from Punta Lobos (PL) on the Pacific coast of BCS and 27 from Punta Arenas (PA) on the Gulf coast. Demographic information was recorded during these interviews, including age, marital status, number and age of children, place of birth, education, years of fishing, alternative sources of income and additional information regarding fishing activity. Graduate students from Centro Interdisciplinario de Ciencias Marinas (CICIMAR) in La Paz, Mexico assisted in the interview process and established on-going relationships with these fishermen.

In our beach sampling program, catch and effort were recorded, with intensive sampling during summer months when fishing activity was greatest. Catch was recorded weekly from as many boats as possible on a standardized form easily completed during a brief interview with fishermen. Additional information collected included vessel, hours fished, fishing area, and species caught. Weight, length, and sex were recorded for landed specimens when possible, and where applicable, stomach and muscle samples were collected for an on-going study of fish trophic ecology.

Results

Seamount inventory

A total of 42 seamounts were found in the central-southern Gulf of California and 24 seamounts in the Pacific off southern Baja California (Figure 1). Of these, nine are deep seamounts (>400m deep), eight intermediate (200-400m deep), thirty-eight are shallow (<200m), nine are shallow reefs (<20m), and two of varying depth (Table 1). Hence, the majority are shallow peaks and reefs. Within the Gulf of California, only two seamounts (4% of total recorded) were found in the northern Gulf (from the Colorado River Delta to the midriff islands), thirty seamounts in the central Gulf (from the midriff islands to the Bay of La Paz), and sixteen seamounts in the southern Gulf. A greater number of seamounts (61%) are located in the central Gulf, which may be due to the larger area, a higher concentration of islands and shallow reefs, and the uneven topography in this portion of the Gulf. The central gulf harbors seamounts at all depths, with the majority of these being shallow (including shallow reefs, 70%) and several deep (20%) and intermediate mounts that give some idea of the rugged topography of this area. A third of the seamounts are located in the southern Gulf, where seamounts at all depths are also found but in lesser numbers compared to the central Gulf. The shallow seamounts and reefs are a majority here, but the deep seamounts are also abundant (25%) in this part of the gulf. The latter is related to wider expanse of deeper water (>2000m) at the mouth of the Gulf of California. In the Pacific, most seamounts are shallow (75%), some are intermediate (17%) and few are deep (8%).

aPositions only reported as an approximation. bDistance of seamount to nearest landmass (continental or large island). cDepth at or near the base of seamount. ‘Scattered seamounts centered at this position. ’Observational cruises conducted by authors including Scuba dives. 2Oceanographic cruises currently being conducted by authors include measurements of primary productivity, nutrients, and plankton and fish communities. D= deep seamount (>400m), I= intermediate seamount (200-400m), S= shallow seamount (<200m), SR= shallow reef (<20m with <35m at its base).

Seasonal abundance of pelagic species

Large multi-species aggregations of fishes were encountered at EBES during all seasons (Table 2). Collectively they formed a seamount assemblage composed of pelagic and migratory reef- associated species that visited the seamount during either the summer and winter, or were resident year-round. We define summer as May through October and winter as November through April. There is strong evidence of the influx of new species during the summer to the seamount environment. The summer assemblage consisted of a jack, Caranx caballus, the dolphinfish, Coryphaena hippurus, and the dog snapper, Lutjanus novemfasciatus, and the scalloped hammerhead shark, Sphyrna lewini. This is evident from the high values, indicating the fraction of visits at that time of the month, for the green jack of 0.96 for June, 0.67 for July, 1.00 for August, and 0.94 for September relative to lower values during the rest of the year. Similarly, the dolphin fish had high values of 0.75 during August and September and 1.00 during October. The yellow snapper was present only briefly at the seamount, with a value of 1.00 for August.

The evidence for a winter assemblage was less compelling. Two species were present exclusively during the winter months, the gulf grouper, Myctoperca jordani, and the yellowtail jack, Seriola lalandi. The gulf grouper most always present from February to April, as evident by the values of 1.00 for these three months. The yellowtail jack was always present during the months of January and February (values of 1.00), yet occurred less frequently at the seamount during March and April (values

The seasonal residency of species at the seamount appeared related to water temperature. The members of the summer assemblage were present at the seamount when the water temperature was high. For example, the dog snapper, a member of the summer assemblage, was most abundant during August and September of 1999, 2000, 2002, and 2003 (see peak positive excursions of dashed black line, Figure 2b), and this coincided with the highest water temperatures recorded at a depth of 30m (see peak negative excursions of black line). Contrastingly, the yellowtail jack was most abundant during January 2000 and 2004 as well as February 2001 and 2003 (see positive excursions of dashed black line, Figure 2a), and this occurred with the lowest water temperatures recorded at the surface (see negative excursions of gray line).

Residence of individuals tagged at EBES ranged from days to months. The four dolphinfish that were tagged remained at the seamount only one day (see solid diamonds to side of "do", Figure 3), consistent with the more nomadic nature of this species. The five green jacks that were tagged remained slightly longer, periods from 4-10 days (see "gj"). The five yellowtail jacks carrying beacons stayed at the seamount for one to two weeks, with one returning after a period of 13 months (see "jt"). Two scalloped hammerhead sharks remained for periods ranging from a single day to 14 days (see "hh"). However, individuals carrying color coded spaghetti tags were observed at EBES for periods ranging from one to three weeks, and single individuals have been observed to return to the seamount one and two years later [32]. The yellowfin tuna exhibited mainly short-term residence of 1-20 days at EBES, but two individuals stayed for period of 23 and 24 months at the site (see "yf").

Socio-economic importance of seamounts

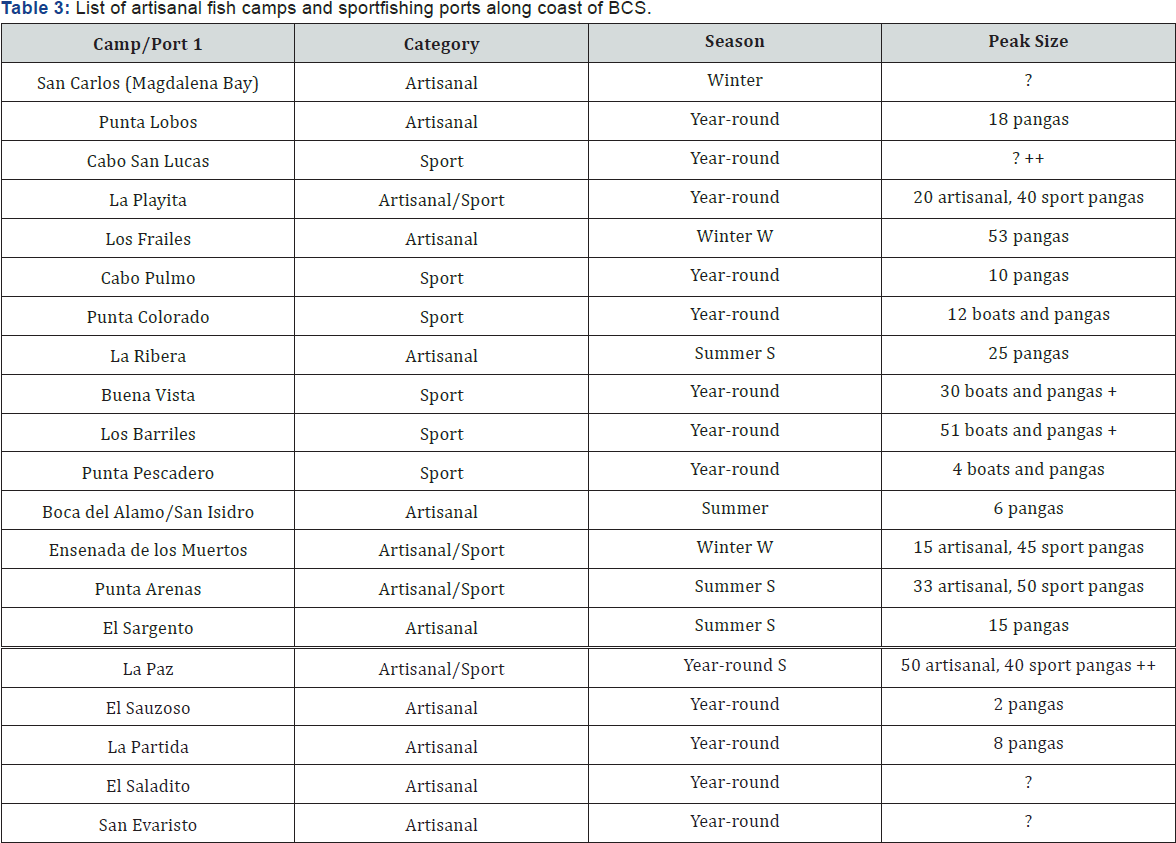

We made 15 trips to five different artisanal fishing camps from January 30- September 14, 2005, at which times we conducted interviews. Interviews were only conducted on 15 of these trips because weather sometimes prohibited fishing. Initial interviews to accumulate demographic information from artisanal fishers were completed for a total of 75 individual fishermen, including 48 interviews in Punta Lobos and 27 interviews in Punta Arenas. When fish camps were mapped in 2002, there were 18 fishing pangas that operated year round near Punta Lobos and 33 pangas that operated during the summer near Punta Arenas (Table 3).

1Camps/ports are in order of location along coast of map in Figure 1, beginning with Magdalena Bay.

?Unsurveyed areas referenced by fishermen, no data is available for these locations.

+ Indicates size of hotel fleet at sportfishing ports, additional private boats may be numerous

++Cabo San Lucas and La Paz are major tourist locations with numerous private sport fishing vessels.

S Large summer camp WLarge winter camp

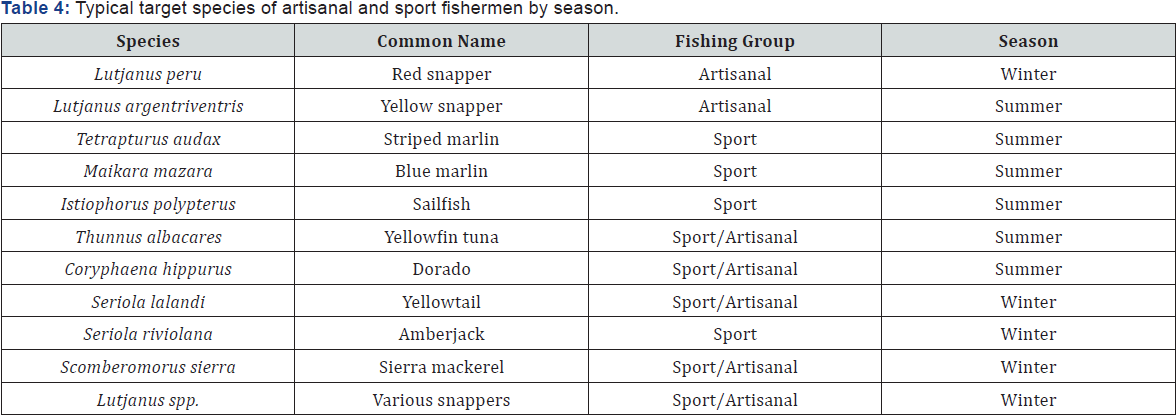

Information from Punta Lobos and Punta Arenas are detailed here. The majority of fishermen at both locations were between 23-49 years old, and most had three to five dependents in their household. Most of those dependents were children, although elderly parents and grandparents were also dependents in the household. 71-74% of fishermen were married, with younger fishermen less likely to be married. In Punta Lobos, fishing was a family custom for 67% of fishermen, while fishing was a family custom for 96% of Punta Arenas fishermen. Ninety-two percent of fishermen live year-round near Punta Lobos in the town of Todos Santos, while fishermen in Punta Arenas are seasonally active and only 70% live in their fishing community throughout the year. Eighty-nine percent of fishermen in Punta Lobos are part of the fishing cooperative, while only 26% of fishermen in Punta Arenas belonged to the cooperative there. Vessels are owned by 26% of fishermen in Punta Arenas own their own vessels, while none of the fishermen interviewed from Punta Lobos owned their boat. In both communities, 98% of a person's income comes from fishing. Ninety-six percent of the catch is sold, and the remaining is for personal consumption. Each fisherman in Punta Lobos had an average of three relatives also dedicated to fishing, while each fisherman in Punta Arenas had an average of six to seven relatives of the same profession. The fishermen performed other jobs to supplement their income at times when fishing was poor (Table 4). Fishermen from Punta Lobos most often farmed when not fishing, while others were masons and athletic coaches. Fishermen at Punta Arenas farmed too, but also raised cattle and were involved in the tourist industry, taking fishermen and divers to local sites.

The largest percentage of fishermen from the fishing settlement of Punta Arena fished during 4-5 months of the year at seamounts in the Gulf of California, but high percentages also fished at seamounts 2-3 months of the year (Figure 4). One fishermen fished more than eight months at local seamounts. The largest percentage of fishermen at Punta Lobos spent 2-3 months fishing at pinnacles off the western coast of the Baja Peninsula in the Pacific Ocean. These are shallow rocky outcroppings, which do not rise from great depths. These artisanal fishermen fished preferentially for yellow snapper during the summer and red snapper during the winter (Table 4). The fishermen also caught dolphinfish and yellowfin tuna to a lesser extent during the summer. During the winter, they also caught yellowtail jacks, sierra mackerel, and other snapper species. The majority of shark fishing occurred at seamounts, while fishing for other species occurred at other areas as well.

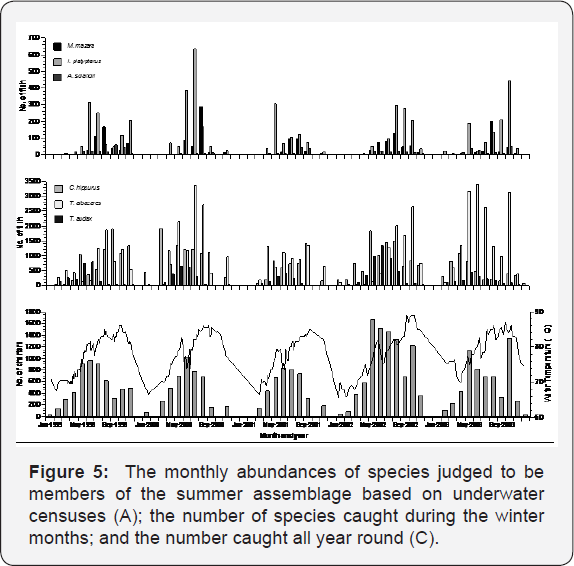

Fishing effort was highest from May through August, and this coincided with the highest water temperatures (see bars and line, Figure 5A). Among billfish, striped marlin comprised the majority of catch and peaked during May 1999, 2000, 2003 and June 2001 and 2002 (see solid bars, Figure 5B). Blue marlin peaked in July or August during all years, while sailfish had three distinct peaks from May to November, depending upon the year. Tuna and dolphinfish were caught all year round, but the highest catches were recorded during late summer during August or September. Snappers and Pacific sierra (figures not shown) were caught almost exclusively in late fall and winter months, with peaks in January and February. Fishermen may capture different species during the winter than during the summer (Table 4). During the winter, they typically fished for red snapper, yellowtail, amberjack, and various snappers, when fishing offshore. These are the same species that were recordedEBES during the winter (see Table 2 &5). During the summer, the fishermen targeted yellow snapper, billfish, yellowfin tuna, and dolphinfish.

Discussion

Seamount definition

We utilize here an inclusive definition of a seamount and prefer not to limit seamounts to those that exceed a considerable distance from shore, rise from substantial depths, or reach a certain distance from the surface [15,33]. We consider a seamount to be any submarine peak or ridge abruptly rising from a level seafloor. It is the topographic nature of the feature that leads to its ecological significance, as a site attracting a diversity of fishes in relatively high abundance [15,16]. This is due to their value as a landmark to its inhabitants [18] as well as their degree of enrichment, most likely dependent upon the interaction of the peak or ridge with moving masses of water [20] and Two types of hydrographic disturbances have been described. The first exists where the oscillating tidal flows are far greater than the continuous wind-driven currents. The tide moves water back and forth and the seamount serves as a stirring rod to cause vertical mixing and disrupt the pycnocline. The second type occurs when the continuous wind-driven flows in one direction far exceed the oscillating tidal flows. This sustained flow past the seamount creates eddies downstream and a wake of disturbed flow extending multiple seamount diameters downstream. The latter hydrographic regime is often present offshore where the ambient flow conditions dominate the smaller tidal variability, but not always so [20,21]. This inclusive definition of seamounts, enables us to consider both the Espiritu Santo Seamount (EBES), which is a ridge rising from a depth of >100m to 15m of the surface 20km from shore, and Gorda Bank Seamount, which is a cluster of pinnacles rising from 300m to 30m from the surface 10km from shore, to be seamounts. They are both sites of great biological enhancement [12].

Seamount inventory

In general, the central and southern Gulf have a greater amplitude, complexity, and steepness of submarine relief (Lonsdale 1984), therefore we concentrate on the occurrence of seamounts in this part of the Gulf. The reduced number of seamounts in the northern Gulf may relate to the fact that a large portion of it is less than 100m deep and the bottom topography is less rugged than the central Gulf due to the large amount of sediment deposited in this region. The continental shelf is much wider off the Pacific shore compared to the eastern shore of the gulf, hence this may be linked with the relatively greater proportion of shallow seamounts and the small proportion of intermediate and deep seamounts in this waters. It is interesting to note, however, the lack of shallow reefs in the Pacific, which may be due to the absence of offshore islands or shallow banks or pinnacles (<20m) throughout the continental shelf and deeper.

Our review of the topography in the Gulf of California has revealed numerous seamounts of varying dimensions and depths. There have been few studies of the diverse topography of the southern Gulf of California, and it is likely that our analysis represents just a small proportion of the seamounts that actually are present in this area. Most bathymetry maps for the region are on a large scale and will miss the fine-scale gradients that can enhance oceanographic conditions and attract assemblages of both reef-associated and pelagic fishes. Fishermen have shown to be a valuable resource for obtaining information on these features.

We have begun studying how pelagic fishes may use some of these features, including in depth studies of EBES [13,19] and Gorda seamount [12] and preliminary observations on a number other seamounts such as 88, Roca Montana, San Francisquito, La Reina (Richert, unpub. data). We and our collaborators have taken a multi-disciplinary approach, to more thoroughly understand the single seamount ecosystem of EBES including analysis of currents [20,21], plankton communities, [17], fish assemblages [18], and feeding habits of fishes and sharks (Richert et al. in prep; Ketchum et al. submitted). Combining these methods enhances our understanding of the ecosystem and would enable an ecosystem-based approach to management. However, continuous study on a variety of scales is needed in order to gain the data necessary for proper management.

While we have located several seamounts and begun study of a few, this region has the potential to examine numerous questions concerning pelagic fish ecology and management [1,2]. The diverse topography and abundance of fishes as well as the dynamic oceanographic conditions that exist in the southern Gulf [23] make this area a natural laboratory at which to study pelagic fish ecology. Seamount oceanographers and ecologist often study seamounts in the middle of oceans or in areas that make logistics of study difficult (i.e. Cobb Seamount) [16]. Further study in this area would help us understand movements and connectedness between seamounts, and perhaps give us an understanding of how fishes migrate and use hotspots on larger scales across ocean basins [1,2].

Seasonal abundance of pelagic species

Some species remain at the EBES seamount for long periods of time, others short periods, and some to return to the same site, exhibiting homing, after periods of multiple months or during the following year. The community structure was stable from year to year, but considerable variability occurred seasonally as members migrated concurrently with strong annual water temperature fluctuations in water temperature. Previously, eighteen hammerheads carrying coded tags, which were monitored over a period two weeks, stayed at the seamount for 4- 5 days before emigrating during upwelling, only to return a week later when warm oceanic water returned to the seamount [12]. In this study, seasonal turnover revealed that the overall community was composed of a summer, winter, and year-round assemblage.

The arrival and departure of certain community members coincided with months of spawning aggregations in the southern Gulf of California. These included members of both the summer and winter groups. The dog snapper, L. novemfasciatus, peaked in September (Figure 2A), when aggregations have been observed spawning at rocky reefs [34]. Apart from these sharp peaks in abundance, the snapper generally were absent from EBES. Sala et al. [34] also reported that yellow tail jack aggregations spawned at reefs and seamounts in April, as evidenced by their high densities and hydrated eggs in gonads. Peak abundance of jacks at EBES occurred between January and April (Figure 2B). The gonads of three females that were caught from a large aggregation on 3 February 2003 had mature gonads with hydrated eggs and the sole male captured released milt as it was brought onboard. At this time, we tagged five other individuals with acoustic transmitters, and they were detected at the seamount for an additional four to 13 days; then they were not detected until one of the tagged individuals was captured by a fisherman at EBES in March of the following year. It seems likely that the seasonal presence of red snapper and yellow-tail jack at EBES was related to spawning activities, although neither species was directly observed spawning.

Fishes clearly aggregate at EBES for multiple reasons, which may include spawning [34], foraging, navigation and social grouping [32]. Genin proposed five mechanisms that aggregate zooplankton, micronekton and fish above seamounts. These mechanisms include elevated primary production caused by upwelling around abrupt topographies as well as behavioral responses of zooplankton related to their vertical migrations. An additional mechanism is driven by the amplification of current over abrupt topographies that increases the prey available to resident fish at these areas. These and possibly other structuring forces resulted in a predictable seasonal changeover of community members at EBES, despite likely similarities among assemblages (i.e., spawning) and differences within assemblages (i.e., foraging versus social grouping). All three assemblages coincided during the warming period between May and August, resulting in the season of highest species richness at the seamount. At this time, the near-surface stratification and the thermal gradient in the upper 30m of the water column were typically strongest. Increased species richness at the seamount occurred during the spring when the surface temperature gradient was highest, and in fall when regional mixing deepened the mixed layer (Table 2 & Figure 2). Seamounts have been proposed as likely places in the oceanic environment for the implementation of marine reserves [2,10]. The resident and homing behavior of pelagic species tagged at EBES suggests that marine reserves sited at such a location may be an effective way to protect pelagic and migratory fish species.

Socio-economic importance of seamounts

Artisanal fish camps in the Gulf of California are usually located near islands and seamounts. This is evident by comparing the locations of the camps on a map of the southern tip of the Baja Peninsula to a chart of the bathymetry in the southern Gulf of California and the Pacific waters off the western coast of the peninsula (Figure 1). The numbers of fishermen present in these camps vary throughout the year, with the camps growing in size when a particular species is plentiful and the catch per effort is high. Some camps are abandoned at certain times of the year, particularly when pelagic fishes are not common in the Gulf of California, or when weather conditions make fishing difficult. To the contrary, sport fishing ports are generally permanent locations, and sport fishermen change target species seasonally (Table 4).

Little conflict was observed among fishing groups. In areas like Punta Arenas and La Playita (San Jose), sport fishermen and artisanal fishermen coexist together on the same beach without conflict. Generally, the small-scale fishing groups target different species (Table 4). Although artisanal fishermen fish for sport species at certain times, there is generally little overlap in the catch of the two groups. Artisanal fishermen generally target the desirable snapper species because the fine-tasting meat is very valuable. However, they will also target certain tunas and jacks when they are abundant in the area. The artisanal fishery usually targets a particular area rather than species. On the other hand, sport fishermen will target particular species and fish optimal areas.

Fisheries catch likely reflects the abundances of species, however caution must be used when using fisheries data as an estimate for fish abundance because it may present a biased sample. In this study, catch was greatest in August and September. Weather and water conditions are generally unstable in the winter and spring. Heavy winds discourage fishermen and make offshore fishing problematic in winter, resulting in lower effort during these months. During spring the winds calm but water conditions are "green" with productivity, and fishing is generally not optimal during this time. However, as summer progresses, the water warms and clears and popular sport species such as the dolphinfish and blue marlin become more abundant. These conditions persist until November or December when the water again cools and the winds blow again. CPUE can be relatively high in winter months because fish are abundant, albeit different inshore species, for those fishermen who brave the winds.

Yellowfin tuna and dorado are perhaps the most desired species for sport fishermen, although billfish are also desirable. Striped marlin are generally the earliest to arrive in the Gulf of California, and the sport catch can be dominated with this species (Figure 5) until yellowfin tuna and dorado arrive in summer time. With increased tuna and dolphinfish catch, a drop in marlin catch is observed. It is unlikely that the striped marlin population abruptly declines, but more likely that fishing effort has shifted to the tuna and dolphinfish. This is an example of why caution must be used in the interpretation of fisheries data. Sport fishermen generally prefer to fish tuna and dolphinfish while they are abundant. In the winter, we see more inshore species captured, such as sierra mackerel which is abundant in the cool winter water but disappears in warmer summer months. It is likely that peak snapper species catch coincides with fishing conditions that cause fishermen to fish near the rocks. For example, a drop in pelagic fish caught may indicate poor weather conditions or poor fishing, so fishermen revert to the dependable snapper species that can be caught in areas sheltered from poor weather. Seamounts are likely less important during the seasons of rough weather, indicating the need to consider the seasonality of fishing in any management strategy in the Gulf of California.

Science-based management of seamount ecosystems

An important issue is resolving that which is required to sustain the populations of fishes that reside at seamounts in the Gulf of California. Sorely needed is science-based management of seamount fish assemblages. Four major areas will need further study if we are to understand and better manage seamount ecosystems and their related fisheries, including:

1. Causation of productivity surrounding seamounts

We need to understand the nature of biological enhancement. Is the enhancement due to an accelerated rate of plankton drift over the seamount due to the increased flows through a confined space that supports a greater biomass of higher level consumers? This would occur when tidal flows dominate at a seamount. Or do continuous currents produce eddies or reverse flow, which trap phytoplankton in the lee of the seamount and support a greater biomass of zooplankton consumers. Is the biological enhancement entirely local in nature, is there importation of larvae of fishes or other members of the zooplankton from distant production centers [17,21].

Scale of oceanographic processes impacting seamounts

The scale of the processes impacting seamounts must be understood. Satellite images of sea surface temperature and chlorophyll will provide a coarse-scale description of the spatial scale of the local enhancement caused by the seamount. Furthermore, satellite imagery can identify large scale eddies of a scale of >10km, which may originate elsewhere but eventually interact with the seamount [12,21]. A fine scale description of the flow interactions of currents with the seamount can be obtained by stationary arrays of hydrographic instruments or surveys carried out from research vessels [20,21].

Connectivity of species to seamounts

We need to know the tenure of residence of higher order consumers such as the billfishes (Istiophoridae), jacks (Carangidae), snappers (Lutjanidae), tunas (Scombridae), and sharks (Carangidae, Sphyrnidae) at these sites. There are summer and winter assemblages that occupy these seamounts (see Jorgensen et al. unpub data). Yet it is unknown how frequently these species move between seamounts during these two seasons. Where do members of the species go when they are not present at the seamount? There is a need to place ultrasonic listening stations at seamounts in the Gulf of California that would record the presence of the individuals, carrying coded ultrasonic tags [18]. These tags could be placed on individuals of pairs of species within both the summer and winter assemblages to ascertain whether species within the assemblages might immigrate or emigrate together in multi-species schools. Tag- detecting arrays are currently being deployed at Cocos Island off Costa Rica, Malpelo Island off Colombia, and Wolf and Darwin Island of the Galapagos archipelago, in order to record whether pelagic fishes migrate in a corridor, consisting of offshore islands, in the Eastern Pacific Ocean. These arrays have been created with funds raised by Conservation International. We need to know the extent of the migrations of the species within these assemblages. Only then can we create an interlocking chain of managed reserves that would ensure that the populations of species remain robust in this region.

Socio-economic impact of ecosystem management on fishermen

Fisheries managers must be provided with rationale for protecting. Their decisions must be based on a science-based understanding of the relationship between fishes and seamounts as well as use of seamounts by fishermen. They must consider the economic significance of the seamounts to different segments of the population. This will require a cost-benefit analysis between commercial fishing and tourism activities [3,9].

We desire to see wise and efficient ecosystem-based management in the Gulf of California, and we believe that such management can only occur if we complete a science-based study focused on these specific areas concerning pelagic fishes and their associated fisheries [35-38].

To Know More About Journal of Oceanography Please Click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/ofoaj/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment