An Unusual and Massive Bloom of Tetraselmis Sp. in the Valparaiso Bay, Chile- Juniper Publishers

Juniper Publishers- Journal of Oceanography

Abstract

An intense bloom of Tetraselmis sp., producing strong water discoloration was observed from December 28th of 2005 through January 10th of 2006 in the Valparaiso Bay (32º 57’S; 71º 33’W). Blooms of Tetraselmis sp. have never been reported in this bay, or along the coast of Chile. The confluence of a series of environmental conditions observed before and during the bloom such as: high solar radiation, anomalous UV radiation levels, high sea surface temperatures, water stratification and high nutrient concentrations may have contributed to the development of this unique event.

Keywords: Bloom tetraselmis sp; High solar irradianc; Positive UV anomaly; Valparaiso bay; Chile

Introduction

Algal blooms are recurring events in coastal regions frequently associated with high nutrients concentrations, particularly of phosphorus and nitrogen. In the Valparaiso Bay, southwesterly winds prevail during the spring and early summer producing upwelling conditions and sporadic phytoplankton blooms, often composed by small diatoms [1]. Blooms of Tetraselmis sp., a microflagellate of the group Prasinophyceae, have never been observed in the Valparaiso Bay waters, or along the coast of Chile. In the Southern Hemisphere only two massive Tetraselmis sp. blooms, producing intense water discoloration have been reported; the first at the Frank Kitts Lagoon, Wellington Harbor, New Zealand on December 10th of 1993, the second at the Saldanha Bay, South Africa on January 15th of 2003 [2,3]. During the bloom at Frank Kitts Lagoon, Tetraselmis sp., reached concentrations from 7.7 x 102 to 1.9 x 103 cells mL-1, other small flagellates such as, Cryptomonas spp. and Pyramimonas spp. were observed at lower concentrations (3.2 x 102 to 5.5 x 102 cells mL-). Water surface temperatures were between 15 °C-15.8 °C, and this was the only environmental parameters measured. During the Saldanha bay bloom, only visual observations were reported. In the Northern Hemisphere, small blooms of Tetraselmis sp. have been frequently observed during the summer at the site of the Harmful Algal Bloom Monitoring Program of the Southern California Coastal Ocean Observing System, San Diego, California (SCCOOS).

The Valparaiso Bay Tetraselmis sp. bloom developed on December 28th of 2005, after a period of calm winds, high solar irradiance, and nutrient concentrations (Nitrates over 30μmL-1 and Phosphates 20μmL-1), cell densities were up to 300 x 103 cellmL-1. The bloom reached a large spatial distribution until January 6th, when nutrient concentrations were near depletion (Phosphates dropped between 0.8-0.3 30μmL-1 and Nitrates below detection). The bloom ended by January 10th of 2006.

Materials and Methods

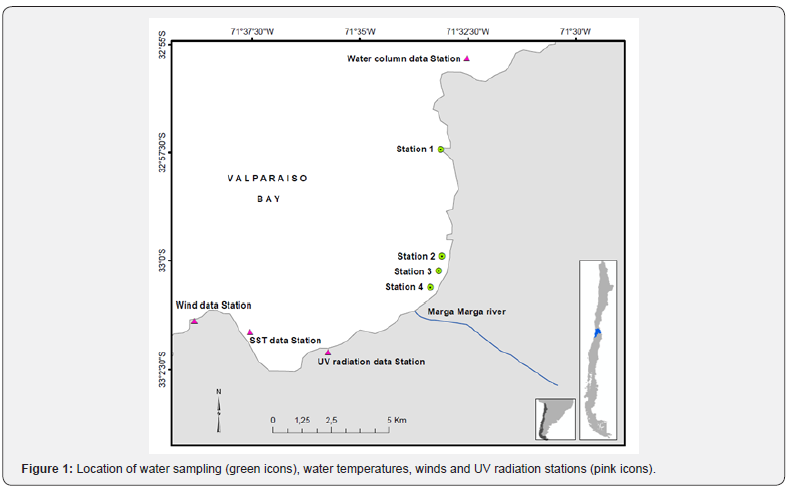

Surface water samples were collected daily from the 2nd to the 6th of January in 2006 at four stations along the Valparaiso Bay coast (Figure 1).

Spectral absorption of suspended particulate matter

The spectral absorption of suspended particulate matter Ap(λ) was determined according to Mitchell [4]. Water samples (25ml, due to the high cell concentrations) were filtered onto Whatman GF/F filters at low vacuum pressure (<2mmHg>). The spectral absorption was determined with a double beam UV-VIS Shimadzu-2500 spectrophotometer. A filter saturated with 0.2μm filtered seawater was used as a blank reference. The contribution of detrital particulates to the total Ap(λ) was determined according to Kishino [5]. The absorption coefficients were calculated using the path-length amplification factor β(λ) described by Mitchell [4].

For data comparison, in situ chlorophyll a, was determined using the relationship between the chlorophyll a specific absorption coefficient (a*pchl a (λ)) and Ap(λ) at 675nm, as follows: (a*pchl a (λ) = Ap(λ)/chl a). A specific absorption coefficient of 0.02 for chlorophyll a was used, thereby making chl a = Ap (λ)/0.02) [6,7]. Concentrations were expressed in mg chl a m-3.

Environmental parameters

Ultra violet radiation (UVR) data were provided by the UV monitoring Station Campbell CR 10X, located 60m above sea level at the Universidad Federico Santa María (33°02’05’’S; 71°35’44’’W). This station is equipped with NR-LITE-CNR1 sensors. UVA and UVB levels are registered every 10 minutes year-round. Sea surface water temperatures and wind data were provided by the Servicio Hidrográfico y Oceanográfico (SHOA), Armada de Chile, and the Gobernación Marítima de Valparaíso, respectively. The first station is located at 33º 01’ 38” S, 71º 37’ 33” W, the second at 33º 01’ 22’’ S, 71º38’50’’ W (Figure 1). Nutrient concentrations were reported by Collantes & Prado [8]. Data for water column temperatures and light attenuation coefficients (Kd) determined with a Secchi disc, were provided by the Universidad de Valparaíso.

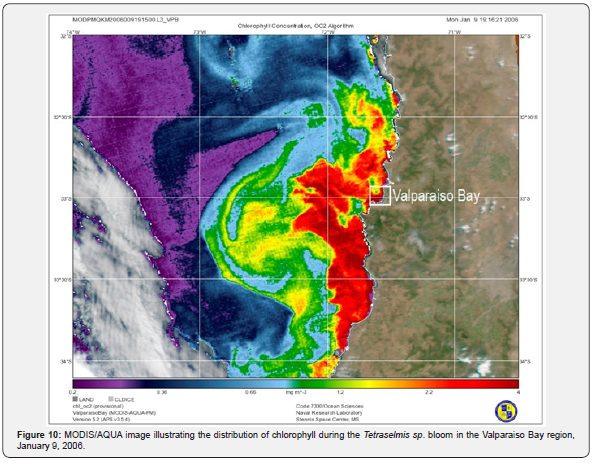

Satellite imagery

An image acquired by the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS/AQUA), during a pass on January 9th of 2006 over the Valparaiso Bay, was utilized to estimate Chlorophyll concentrations and geographical distribution. MODIS level 1b products from this image were obtained from the NASA archives and converted into Chlorophyll a, using the Automated Processing System (APS) at the Naval Research Laboratory, Stennis Space Center, Mississippi (NRL-SSC). This is a fully automated software package able of processing data for most of the ocean color sensors, delivering accurate Level III and IV products [8,9].

Results

Spectral Absorption of suspended particulate matter

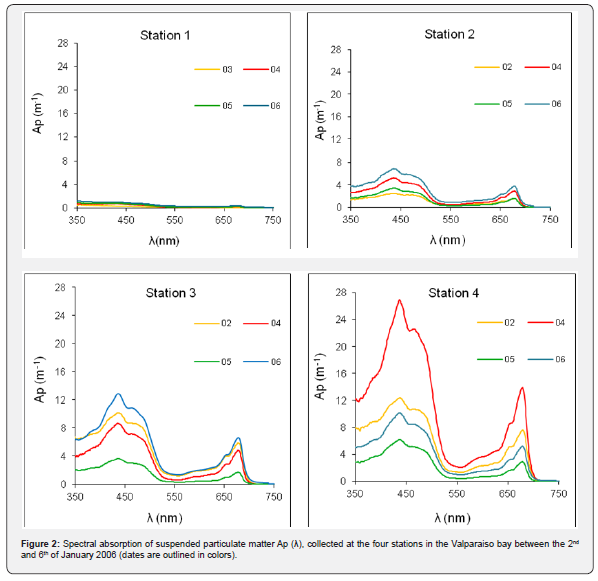

The bloom was unique for its magnitude and monoculture type resemblance as shown by the Ap(λ) and shape of the spectra. The Ap(λ) values reflect the cell concentrations and the shape of the spectra, which highlights the absorption peaks of chlorophyll a, at 440nm and 675nm, and chlorophyll b at 470nm and 650nm. Chlorophyll b is distinctive of the Prasinophyceae taxonomic group. These spectral markers were observed in all samples during the bloom (Figure 2).

The contribution of detrital matter to the total Ap (λ) was low (0.2 to 0.8m-1 at 350nm and less than half at 450nm), indicating that cellular material was one of the main components within the suspended particulate matter.

The maximum Ap (λ) values were observed at station 4 on January 4th. This site is located in the proximity of the Marga Marga river small outfall, where conditions for a higher proliferation of Tetraselmis sp. appeared to be optimal that day. The lowest Ap (λ) values were observed at Station 1. Chlorophyll a in vivo concentrations estimates ranged between 11 to 18mg m-3 at Station 1, between 78 to 142mg m-3 at Station 2, between 82 to 292mg m-3 at Station 3 and from 237mg m-3 to a maximum of 678mg m-3 at Station 4 (Figure 2).

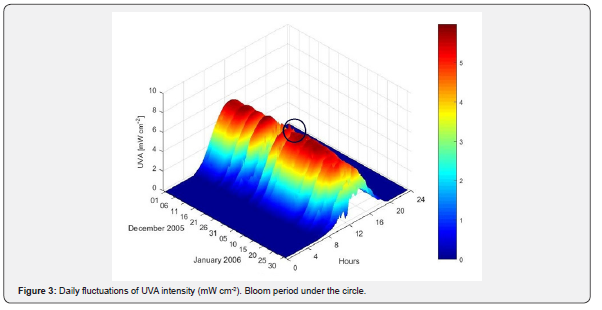

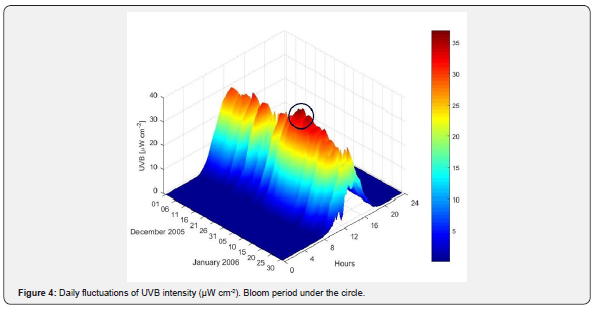

UVA-UVB radiation

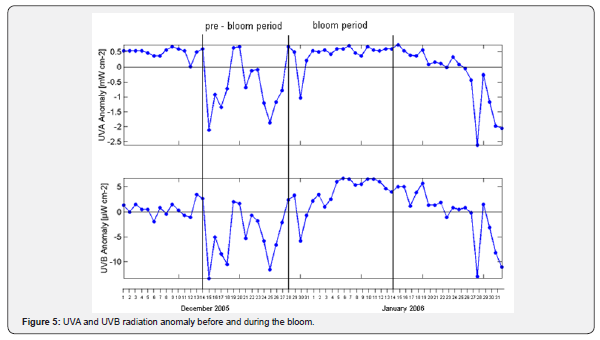

During the pre-bloom period (December 14th through the 27th of 2005), UVA levels increased from 3.11 to 5.8mW cm-2 and UVB from 15.49 to 30.31μW cm-2 (Figures 3 & 4). During the bloom period (December 28th to approximately January 10th), UVB radiation continued to rise up to 36.94μW cm-2 on January 6th of 2006, while UVA levels remained steady. During the pre-and bloom periods, UVA and UVB reached their highest intensities at midday.

Data collected from 2001 through 2006 during the months of January and July were used to determine the patterns of UVR levels at different times scales (daily, monthly, annually) and to select the periods when the maximum and minimum UVA and UVB intensities were above the average. At mid latitudes, the months of January and July represent the highest and the lowest solar radiation levels registered during all seasons. An anomaly refers to values that are above average (positive anomaly), or below (negative anomaly) within a period. The daily anomaly for the Valparaiso bay was calculated using an average of the daily UVA and UVB radiation levels.

During the pre-bloom period, short-term anomalies for UVA and UVB were registered. However, during the bloom period the magnitude of the positive anomaly for UVB remained in the order of ~ 2.5 - 5μW cm-2, the UVA anomaly remained without major changes at 0.5mW cm-2 (Figure 5).

Light attenuation coefficient (Kd):

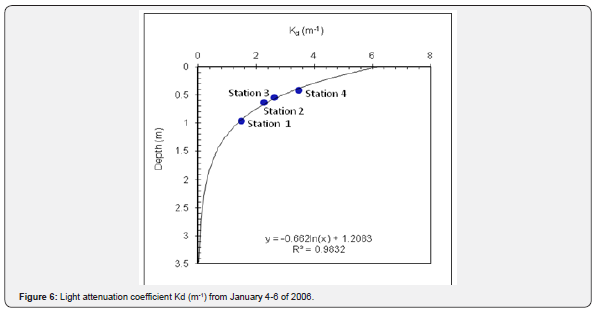

The high Kd values observed in the coastal areas indicated that Tetraselmis sp. cells reached their maximal growth at the surface and remained in the upper surface during the bloom, restricting the euphotic zone to the upper 3.5 meters. Photosynthetic activity of non-motile phytoplankton (e.g., diatoms) unable to migrate to the surface, may have been affected by the low light levels prevailing below that depth (Figure 6). Previous Kd values for the Valparaiso Bay fluctuated between 0.68m-1 and 0.1m-1[9].

Sea surface temperature

During the pre-bloom period, sea surface temperatures oscillated between 16 °C and 18.6 °C. During the bloom period, they reached a maximum of 19 °C on January 6th (Figure 7).

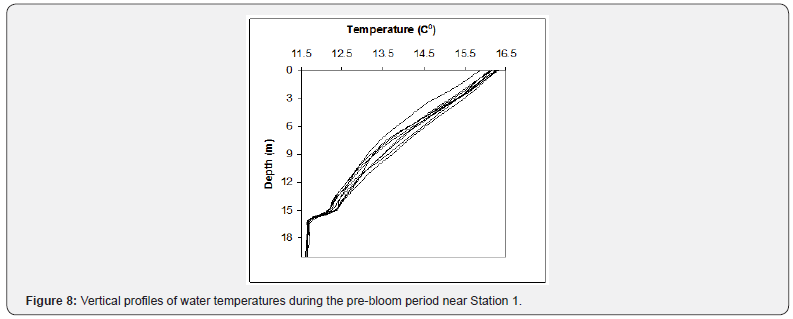

A water temperature profile performed near the coast on December 27th indicated that a distinctive thermocline had started to develop at 16m depth. Taking into account that sea surface temperatures continued to increase until January 6th, a shallower thermocline and mixed layer are expected to have developed in the coastal waters of the bay (Figure 8).

Winds

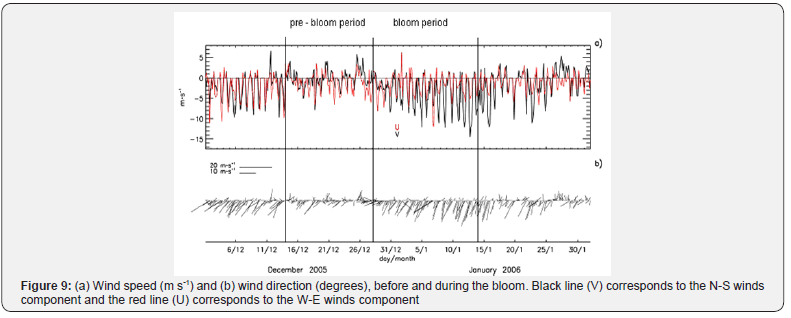

During the pre-bloom period, weak southwesterly (SW) and northerly (N) winds predominated. Daily wind speed averaged from 1.85ms-1 to 5ms-1, remaining calm during the bloom period. By January 10th the wind direction (SW) increased over 13m s-1, coinciding with the end of the bloom (Figure 9). Wind speeds within the range of 15-10m s-1 generate upwelling conditions in the Valparaiso Bay [10-14].

Remote sensing analyses

The MODIS/AQUA image illustrates the extent and distribution of the bloom spreading latitudinally along the coast of the Valparaiso Bay from 32° to 34° N, and longitudinally from the coast line to 72° W. As a result of the high chlorophyll concentrations in the coastal waters (above 4.0mg m-3), the color gradient fell out of scale. In offshore waters, chlorophyll estimates were in the range of 0.2mg m-3, with fringes extending to the north and south. However, no in situ chlorophyll determinations were performed to cross-validate these estimates (Figure 10).

There was an indication of a clockwise circulation delineated by the chlorophyll concentrations between 1 and 2mg m-3. The presence of such cold eddies may have had some role in the encroachment of coastal waters during the pre- and bloom periods. Outside of the eddy-like circulation, chlorophyll concentrations were below 0.5mg m-3, values commonly observed in offshore waters of this region. However, due to the extensive cloud cover, common along the coast of Chile, it was not possible to follow the development of eddies from satellite imagery.

Discussion

The Valparaiso Bay Tetraselmis sp. bloom occurred in the middle of the summer season of the southern hemisphere. The bloom developed rapidly after a period of wind relaxation, high solar irradiance, higher water temperatures, stratification of the upper water column, as well as high nutrient concentrations. The confluence of all these factors, in addition to a positive UVR anomaly may have provided a unique scenario for the development of this massive bloom.

A comparison of previous records of sea surface temperatures in the Valparaiso Bay during December and January indicated an average within 15-17 °C [11,14]. During the pre-bloom period of Tetraselmis sp., sea surface temperatures registered 18 °C, reaching 19 °C during the bloom. Nutrient concentrations during the pre-bloom period was in the order of 30μm L-1 and 46μm L-1 for nitrate and phosphate respectively. Such high concentrations facilitated the high cell density observed along the coast of the bay during the bloom. At Station 4, cell concentrations reached 300 x 103 cell mL-1, with chlorophyll a values of 642mg m-3. These values superseded an intense red tide bloom of Lingulodinium polyedra observed in La Jolla, California, in 1995, where cell concentrations reached 20 x 103 cell mL-1 and surface chlorophyll a exceeded 100mg m-3, with one observation reaching 500mg m-3 [15]. Several dinoflagellate blooms with cell concentrations in the order of 2 x 103 cell mL-1 and chlorophyll a values of 500mg m-3, were reported for this same area during 1964, 1965 and 1966 [16]. In the Valparaiso Bay, during a typical spring season upwelling, previous data for nutrient concentrations indicated values between 3 and 9μmL-1 for nitrate and between 2 and 3μmL-1 for phosphates. However, chlorophyll a concentrations fluctuated between 0.9 to 31mg m-3 [13]. During the Valparaiso Bay pre-bloom period nitrates and phosphates reached values over 30μmL-1 and 20μmL-1. Wind speed measured during the preand bloom periods remained calmed facilitating water column stratification, only near the end of the bloom wind speed reached values over 13m s-1, typical upwelling conditions for the Valparaiso Bay develop when wind speeds reach between 15 - 20m s-1 [13].

The high attenuation coefficient, Kd (m-1), observed during the Valparaiso Bay bloom indicated that Tetraselmis sp. cells proliferated and remained approximately in the upper 3 meters. Photosynthetic activity of non-motile species (e.g. diatoms) unable to migrate to the surface may have been affected by the low light levels prevailing below that depth (Kd values at Station 1 and station 4, between 1.5m-1 to 3.5m-1, respectively). The values were much higher when compared to previous Kd measurements for the bay that fluctuating between 0.68m-1 and 0.1m-1 [10].

Another factor to be considered was the high UVR levels and positive UV anomaly observed before and during the bloom. Photosynthesis is affected by the levels of photosynthetically active radiation (PAR: 400–700nm) and ultraviolet radiation (UVR: 290– 400nm) penetration in the upper water column. Excessive PAR and UVR inhibit photosynthesis and damage cellular components [17-22]. UVB (290nm-320nm) radiation has raised concerns for its effects on marine ecosystems [23,24]. An increase in UVB can alter species composition and standing crop of microalgae [25-27]. Though, species with micosporin-like-aminoacids (MAA) cellular content are more tolerant to higher UVB levels [24,28-30]. Previous studies have indicated that Tetraselmis sp. is able to sustain and grow under higher UVR levels than other phytoplankton. Experimental data showed no evidence of delay in cellular division of Tetraselmis sp. under solar radiation dosages of 416cal cm-2 d-1 for five days, showing a high tolerance to UVR [25]. Furthermore, a study about the relative sensitivity to UVB by Tetraselmis suecica, showed no inhibition to dosages of 0.4 Wm-2 [31]. These studies suggest that under experimental conditions this specie is tolerant to higher UVR levels [32,33]. However, the extent of UVR damage to the phytoplankton community, has not yet been resolved [34].

Conclusion

Information about Tetraselmis sp. massive blooms are restricted to the few previous observations, they are also limited by the lack of long-term oceanographic data available, including the one observed at the Valparaiso Bay. Therefore, it is difficult to formulate unambiguous conclusions without falling into speculations. Although, we can assume that the simultaneous confluence of high solar irradiances, sea surface temperatures, water column stratification, high nutrient concentrations, and a positive UV anomaly after a period of wind relaxation, facilitated the rapid growth Tetraselmis sp., outpacing other species. A relevant feature about this bloom, was provided by the MODIS/ Aqua image revealing the magnitude and distribution of this bloom. What remains unknown is the phytoplankton composition beyond the Valparaiso Bay coastal waters.

For more about Juniper Publishers please click on: https://twitter.com/Juniper_publish

For more about Oceanography & Fisheries please click on: https://juniperpublishers.com/ofoaj/index.php

Comments

Post a Comment